Have you noticed your arms looking thinner, your legs losing definition, or your buttocks becoming less toned? You’re not alone. Muscle mass naturally declines with age and inactivity, with studies showing that adults lose 3-8% of muscle mass per decade after age 30—a condition known as sarcopenia. But age isn’t the only culprit. Sedentary lifestyles, poor nutrition, chronic illnesses, and even stress can accelerate muscle loss, leaving you feeling weaker, fatigued, and more prone to injuries.

What’s more concerning is the ripple effect of muscle loss. It doesn’t just impact your physical appearance; it compromises strength, mobility, and overall health. For instance, research reveals that severe muscle loss can lead to a 30% decrease in strength, making everyday tasks like climbing stairs or lifting groceries challenging. Yet, the good news is that muscle atrophy isn’t irreversible. By identifying the causes and taking proactive steps, you can rebuild lost muscle and regain vitality.

In this guide, we’ll dive deep into the causes of muscle atrophy, the warning signs to look out for, and actionable strategies to restore and maintain muscle health. Let’s uncover how to reclaim your strength and live life to the fullest!

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the causes, signs, and strategies for reversing muscle loss and rebuilding strength effectively.

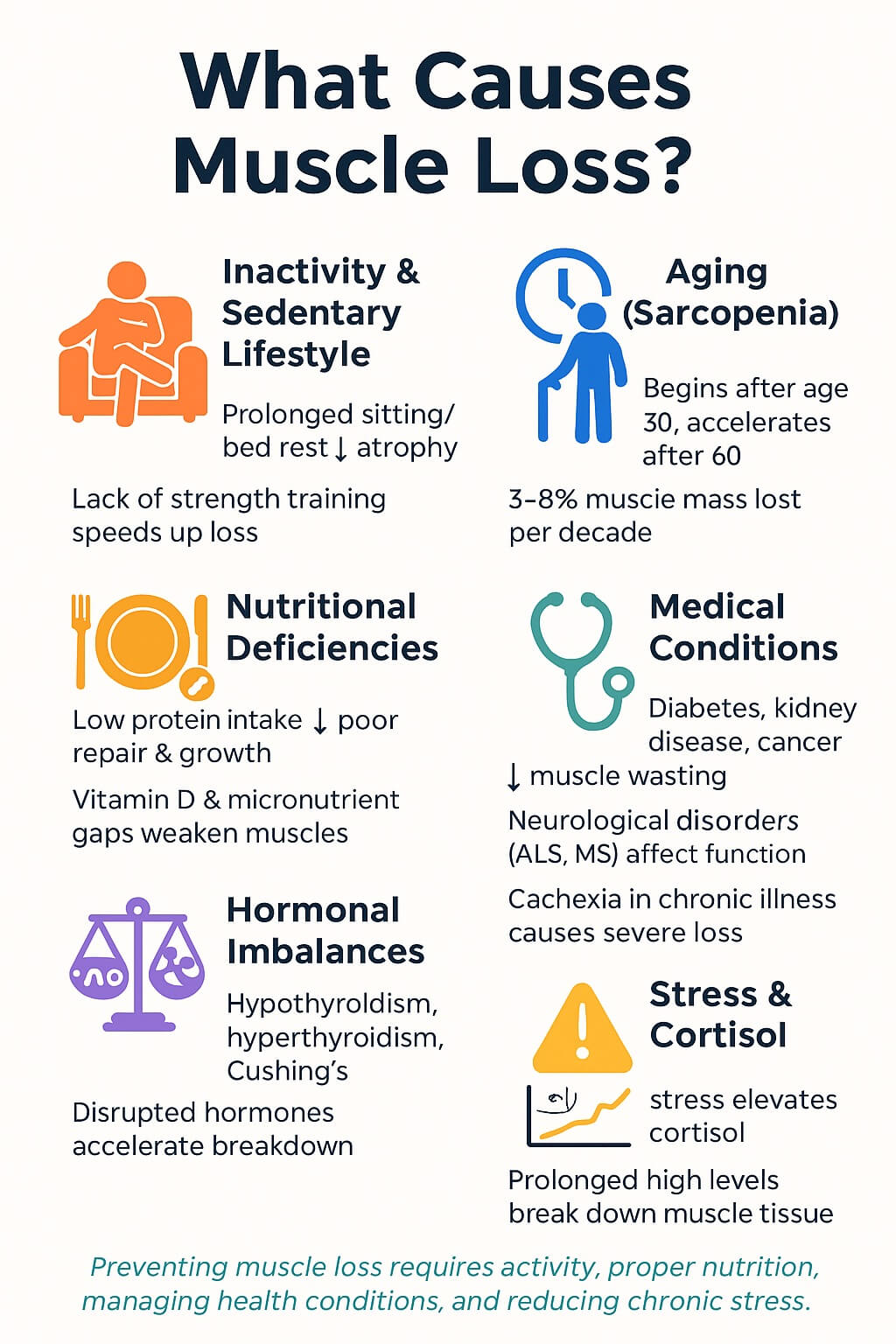

What Causes Muscle Loss?

Muscle loss, or muscle atrophy, represents a complex physiological process that can significantly impact quality of life, functional capacity, and overall health outcomes. This condition results from an imbalance between muscle protein synthesis and muscle protein breakdown, where the rate of tissue degradation exceeds the body’s ability to rebuild and maintain muscle mass. Understanding the multifaceted causes of muscle loss is crucial for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies, particularly as populations age and sedentary lifestyles become increasingly prevalent.

Inactivity and Sedentary Lifestyle: The Modern Epidemic

Physical inactivity stands as one of the most preventable yet widespread causes of muscle loss in contemporary society. When muscles are not regularly challenged through movement and resistance, they begin to atrophy remarkably quickly. Research demonstrates that complete bed rest can result in a devastating 1-5% loss of muscle mass per day, with the most significant losses occurring in the weight-bearing muscles of the legs and core. This rapid deterioration occurs because muscles operate on a “use it or lose it” principle – without mechanical stimulation, the body perceives muscle tissue as metabolically expensive and unnecessary.

The sedentary lifestyle epidemic extends far beyond complete inactivity. Modern work environments that require prolonged sitting, combined with leisure activities centered around screens, create conditions of chronic underuse. Even individuals who consider themselves active may experience muscle loss if their daily activities lack sufficient resistance or load-bearing components. The absence of strength training is particularly detrimental, as resistance exercise provides the specific stimulus needed to maintain and build muscle mass. Without this stimulus, muscle fibers begin to shrink, motor units become less efficient, and the neuromuscular system gradually loses its capacity for force production.

Aging and Sarcopenia: The Inevitable Decline

Sarcopenia, the age-related loss of muscle mass and function, represents one of the most significant health challenges facing aging populations worldwide. This process typically begins subtly around age 30, when adults start losing approximately 3-8% of their muscle mass per decade. However, the rate of loss accelerates dramatically after age 60, with some individuals losing up to 15% of their muscle mass per decade in later years. This isn’t merely a cosmetic concern – sarcopenia directly correlates with increased risk of falls, fractures, disability, and mortality.

The mechanisms underlying age-related muscle loss are complex and multifaceted. Hormonal changes play a crucial role, with declining levels of anabolic hormones such as testosterone, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor-1 reducing the body’s ability to build and maintain muscle tissue. Simultaneously, the aging process affects muscle protein synthesis at the cellular level, making older adults less responsive to the muscle-building effects of protein consumption and exercise. Changes in the nervous system also contribute, as motor neurons that control muscle fibers begin to die off, leading to a reduction in muscle fiber number and size. Additionally, chronic low-grade inflammation, common in aging, creates a catabolic environment that favors muscle breakdown over synthesis.

Nutritional Deficiencies: Starving the Muscle

Proper nutrition serves as the foundation for muscle health, providing both the raw materials for muscle protein synthesis and the energy required for optimal muscle function. Protein deficiency stands as the most obvious nutritional cause of muscle loss, as muscles require a constant supply of amino acids to maintain their structure and function. The recommended dietary allowance for protein may be insufficient for older adults or those trying to maintain muscle mass, with research suggesting that higher intakes of 1.2-1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight may be more appropriate.

However, muscle health depends on far more than protein alone. Vitamin D deficiency, increasingly common in populations with limited sun exposure, significantly impairs muscle function and strength. This vitamin acts not only as a hormone regulating calcium metabolism but also directly influences muscle protein synthesis and neuromuscular function. Deficiencies in other nutrients, including magnesium, potassium, and B vitamins, can also compromise muscle health. Chronic malnutrition, whether from inadequate caloric intake or poor food choices, forces the body to break down muscle tissue to meet its energy and nutrient needs, creating a catabolic state that perpetuates muscle loss.

Medical Conditions: When Disease Attacks Muscle

Numerous medical conditions can directly or indirectly cause significant muscle loss, often through complex pathophysiological mechanisms. Chronic diseases such as diabetes create a state of chronic inflammation and insulin resistance that impairs muscle protein synthesis while promoting protein breakdown. Cancer and its treatments represent particularly severe threats to muscle mass, with cachexia – a syndrome of severe muscle and weight loss – affecting up to 80% of advanced cancer patients. This condition involves complex interactions between tumor-derived factors, inflammatory cytokines, and metabolic dysfunction that create an environment of accelerated muscle wasting.

Kidney disease leads to muscle loss through multiple pathways, including chronic acidosis, inflammation, decreased appetite, and uremic toxins that interfere with muscle metabolism. Neurological disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis, or spinal cord injuries cause muscle loss through denervation – the loss of nerve supply to muscles. Without neural stimulation, muscles rapidly atrophy and lose function. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) causes muscle loss through systemic inflammation, reduced physical activity due to breathlessness, and the increased energy cost of breathing that diverts resources from muscle maintenance.

Hormonal Imbalances: The Chemical Messengers Gone Wrong

The endocrine system plays a critical role in regulating muscle mass through various hormonal pathways. Thyroid disorders exemplify how hormonal imbalances can dramatically affect muscle tissue. Hyperthyroidism accelerates muscle protein breakdown while potentially impairing synthesis, leading to rapid muscle wasting despite normal or increased appetite. Conversely, hypothyroidism can cause muscle weakness and reduced muscle quality, though the mechanisms differ from hyperthyroidism.

Cushing’s syndrome, characterized by excessive cortisol production, demonstrates the powerful catabolic effects of glucocorticoids on muscle tissue. Cortisol promotes muscle protein breakdown while simultaneously inhibiting protein synthesis, creating a perfect storm for muscle loss. This condition often results in characteristic patterns of muscle wasting, particularly affecting the proximal muscles of the arms and legs. Diabetes mellitus, while primarily a metabolic disorder, significantly impacts muscle health through chronic hyperglycemia, which impairs muscle protein synthesis and promotes the formation of advanced glycation end products that damage muscle tissue.

Stress and Cortisol: The Silent Muscle Destroyer

Chronic psychological and physical stress represents an often-overlooked contributor to muscle loss through the persistent elevation of cortisol levels. While cortisol serves important functions in acute stress responses, chronically elevated levels become destructive to muscle tissue. This hormone promotes gluconeogenesis – the production of glucose from non-carbohydrate sources, including muscle protein – while simultaneously inhibiting muscle protein synthesis. The result is a net loss of muscle mass over time.

Modern life presents numerous sources of chronic stress, from work pressures and financial concerns to relationship difficulties and health worries. Sleep deprivation, itself a form of physiological stress, compounds these effects by disrupting the normal hormonal rhythms that support muscle recovery and growth. The stress-muscle loss connection creates a vicious cycle, as muscle loss can lead to functional decline and reduced quality of life, which in turn generates more stress and further muscle loss. Breaking this cycle requires addressing both the sources of stress and implementing strategies to support muscle health through proper nutrition, exercise, and stress management techniques.

Signs of Losing Muscle Mass

Recognizing muscle loss early is crucial for addressing it effectively. Common signs include a noticeable reduction in muscle size, decreased strength, and increased fatigue during everyday activities. Studies show that individuals with significant muscle loss may experience up to a 30% decline in physical strength over time. Balance and mobility issues are also common, as muscle mass contributes significantly to stability and coordination. Unexplained weight loss, particularly when accompanied by sagging skin or thinning limbs, can indicate muscle atrophy rather than fat loss. Research highlights that muscle loss affects 5-13% of older adults annually, underscoring the importance of monitoring these signs to maintain physical health and function.

Recognizing the signs of muscle loss early can make a big difference in preventing further decline. One of the first clues is decreased strength, where everyday activities such as lifting groceries, climbing stairs, or even opening jars start to feel more challenging. You may also notice a thinner appearance, with reduced muscle size in the arms, thighs, or buttocks, sometimes making clothes feel looser even if your weight hasn’t changed much.

Another common symptom is persistent fatigue—feeling unusually tired after light activities like walking a short distance or completing simple chores. This is because reduced muscle mass limits your body’s energy reserve and endurance. Along with fatigue, balance and mobility issues often appear. Tasks such as standing up from a chair without using your hands, or climbing stairs without holding onto a railing, can become difficult, and the risk of tripping or falling increases.

In some cases, there may be unexplained weight loss that isn’t linked to changes in diet or exercise. This type of weight loss often reflects muscle wasting rather than fat reduction, especially in older adults or those with chronic illnesses. Finally, sagging or loose skin—particularly around the arms, thighs, and abdomen—can be another visible sign, as the loss of muscle volume leaves the skin less supported.

How to Improve Muscle Loss

Improving muscle loss requires a combination of targeted exercise, proper nutrition, and lifestyle changes. Strength training is vital, with studies showing it can increase muscle mass by 1–3% per week when performed consistently. Aim for at least two sessions per week, focusing on major muscle groups with resistance exercises like squats, lunges, and push-ups. Nutrition plays a key role; consuming 1.2–2.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily can significantly support muscle repair and growth. Additionally, staying active with regular physical activities like walking or swimming can slow muscle loss, while managing stress and maintaining adequate vitamin D and calcium levels help sustain muscle health. Combining these strategies can reverse mild to moderate muscle atrophy and restore strength over time.

Rebuilding muscle mass involves a combination of exercise, nutrition, and lifestyle changes. Here’s how you can improve muscle health effectively:

1. Strength Training Exercises

- Focus on resistance exercises such as weightlifting, bodyweight exercises, and resistance bands.

- Target major muscle groups, including the arms, legs, and glutes, with compound movements like squats, lunges, push-ups, and deadlifts.

- Start with light weights and gradually increase the intensity.

2. Adequate Protein Intake

- Protein is crucial for muscle repair and growth. Aim for 1.2 to 2.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily.

- Include lean protein sources like chicken, fish, eggs, beans, and tofu in your diet.

3. Stay Active

- Incorporate regular physical activity, such as walking, cycling, or swimming, to prevent muscle atrophy caused by inactivity.

- Even short daily movements can make a difference.

4. Proper Nutrition

- Eat a balanced diet rich in complex carbohydrates, healthy fats, and essential vitamins and minerals.

- Ensure you’re getting enough calcium and vitamin D for muscle and bone health.

5. Manage Stress

- Practice stress-reducing activities like yoga, meditation, or deep breathing to lower cortisol levels and protect muscle tissue.

6. Consult a Specialist

- If muscle loss is severe or linked to a medical condition, seek advice from a doctor or physical therapist.

- A healthcare provider may recommend specific treatments, such as physical therapy, medications, or hormone replacement therapy.

Can Muscle Atrophy Be Reversed?

Yes, muscle atrophy can often be reversed with the right interventions, especially if addressed early. Studies indicate that resistance training can increase muscle strength by 25-100% over 3-6 months in individuals with muscle loss, depending on the severity. Adequate protein intake, at least 1.2–2.0 grams per kilogram of body weight daily, plays a critical role in supporting muscle repair and growth. For age-related atrophy, engaging in regular strength training can slow the progression by up to 50%, according to research. In cases of severe muscle loss caused by illness or injury, physical therapy and medical interventions may be necessary. Early and consistent efforts, including exercise, proper nutrition, and addressing underlying causes, are key to successfully reversing muscle atrophy.

The good news is that muscle atrophy can often be reversed with the right interventions. Rebuilding muscle takes time, consistency, and a proactive approach:

- Mild to Moderate Muscle Loss: Can be reversed with strength training, improved nutrition, and lifestyle adjustments.

- Severe Muscle Loss: May require medical treatments or rehabilitation programs.

Early intervention is key. The sooner you address muscle loss, the better your chances of restoring strength and function.

Losing muscle mass in your arms, legs, and buttocks can be alarming, but it’s not an irreversible condition. By understanding the causes and adopting targeted strategies such as strength training, proper nutrition, and stress management, you can rebuild your muscles and regain your strength.

If you’ve noticed signs of muscle loss, take action today. Your body—and your future self—will thank you.

Citations and References

Foundational Research on Sarcopenia and Age-Related Muscle Loss

- Rosenberg, I.H. (1997). “Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance.” Journal of Nutrition, 127(5), 990S-991S.

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J., et al. (2019). “Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis.” Age and Ageing, 48(1), 16-31.

- Lexell, J., et al. (1988). “What is the cause of the ageing atrophy? Total number, size and proportion of different fiber types studied in whole vastus lateralis muscle from 15- to 83-year-old men.” Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 84(2-3), 275-294.

Inactivity and Bed Rest Studies

- Wall, B.T., et al. (2013). “Skeletal muscle atrophy during short-term disuse: implications for age-related sarcopenia.” Ageing Research Reviews, 12(4), 898-906.

- Kortebein, P., et al. (2007). “Effect of 10 days of bed rest on skeletal muscle in healthy older adults.” JAMA, 297(16), 1772-1774.

- Dirks, M.L., et al. (2014). “One week of bed rest leads to substantial muscle atrophy and induces whole-body insulin resistance in the absence of skeletal muscle lipid accumulation.” Diabetes, 63(10), 3409-3420.

Muscle Protein Synthesis and Breakdown

- Phillips, S.M., et al. (2009). “Resistance training reduces the acute exercise-induced increase in muscle protein turnover.” American Journal of Physiology, 276(1), E118-E124.

- Cuthbertson, D., et al. (2005). “Anabolic signaling deficits underlie amino acid resistance of wasting, aging muscle.” FASEB Journal, 19(3), 422-424.

Nutrition and Protein Requirements

- Bauer, J., et al. (2013). “Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group.” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 14(8), 542-559.

- Moore, D.R., et al. (2009). “Ingested protein dose response of muscle and albumin protein synthesis after resistance exercise in young men.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89(1), 161-168.

- Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A., et al. (2009). “Fall prevention with supplemental and active forms of vitamin D: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” BMJ, 339, b3692.

Medical Conditions and Muscle Wasting

- Fearon, K., et al. (2011). “Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus.” The Lancet Oncology, 12(5), 489-495.

- Wang, X.H., et al. (2006). “Metabolic acidosis promotes muscle wasting in uremia by activating the ATP-dependent ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.” Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 17(5), 1388-1394.

- Schakman, O., et al. (2013). “Glucocorticoid-induced skeletal muscle atrophy.” International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 45(10), 2163-2172.

Hormonal Influences on Muscle Mass

- Sinha-Hikim, I., et al. (2002). “The use of a sensitive equilibrium dialysis method for the measurement of free testosterone levels in healthy, cycling women and in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 83(4), 1312-1318.

- Giannoulis, M.G., et al. (2012). “Hormone replacement therapy and physical function in healthy older men. Time to talk hormones?” Endocrine Reviews, 33(3), 314-377.

Exercise Interventions and Muscle Building

- Peterson, M.D., et al. (2010). “Resistance exercise for muscular strength in older adults: a meta-analysis.” Ageing Research Reviews, 9(3), 226-237.

- Fiatarone, M.A., et al. (1994). “Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people.” New England Journal of Medicine, 330(25), 1769-1775.

- Leenders, M., et al. (2013). “Prolonged leucine supplementation does not augment muscle mass or affect glycemic control in elderly type 2 diabetic men.” Journal of Nutrition, 143(8), 1183-1189.

Stress, Cortisol, and Muscle Loss

- Duclos, M., et al. (2003). “Cortisol and GH: odd and controversial ideas.” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 28(5), 783-803.

- Chrousos, G.P. (2009). “Stress and disorders of the stress system.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 5(7), 374-381.

Diagnostic Criteria and Assessment

- Studenski, S.A., et al. (2014). “The FNIH sarcopenia project: rationale, study description, conference recommendations, and final estimates.” The Journals of Gerontology Series A, 69(5), 547-558.

- Cawthon, P.M., et al. (2018). “Sarcopenia: consensus definitions, prevalence, and associated health outcomes.” Current Opinion in Rheumatology, 30(6), 636-641.

Prevention and Treatment Guidelines

- Denison, H.J., et al. (2015). “Prevention and optimal management of sarcopenia: a review of combined exercise and nutrition interventions to improve muscle outcomes in older people.” Clinical Interventions in Aging, 10, 859-869.

- Landi, F., et al. (2016). “Muscle loss: the new malnutrition challenge in clinical practice.” Clinical Nutrition, 35(5), 1073-1077.

Pingback: How to Fix Aging Lips: Expert Tips, Natural Remedies, and Effective Treatments - Wellness Readers Digest

Pingback: How Much Protein Do You Really Need To Get Strong? - Wellness Readers Digest