Sitting down with a book you used to love only to realize you’ve read the same paragraph three times without absorbing a single word feels frustrating and alienating. Your mind wanders before you finish a sentence. Coloring books that promise relaxation hold your attention for barely five minutes. Your phone becomes a compulsive security blanket, checked hundreds of times daily without actually engaging with any content. This isn’t laziness or lack of intelligence. It’s a documented consequence of prolonged stress that fragments attention and impairs the brain’s ability to sustain focus. The good news is that attention span can be rebuilt, though the process requires patience and strategies that work with your current capacity rather than against it.

Why does stress destroy your ability to focus?

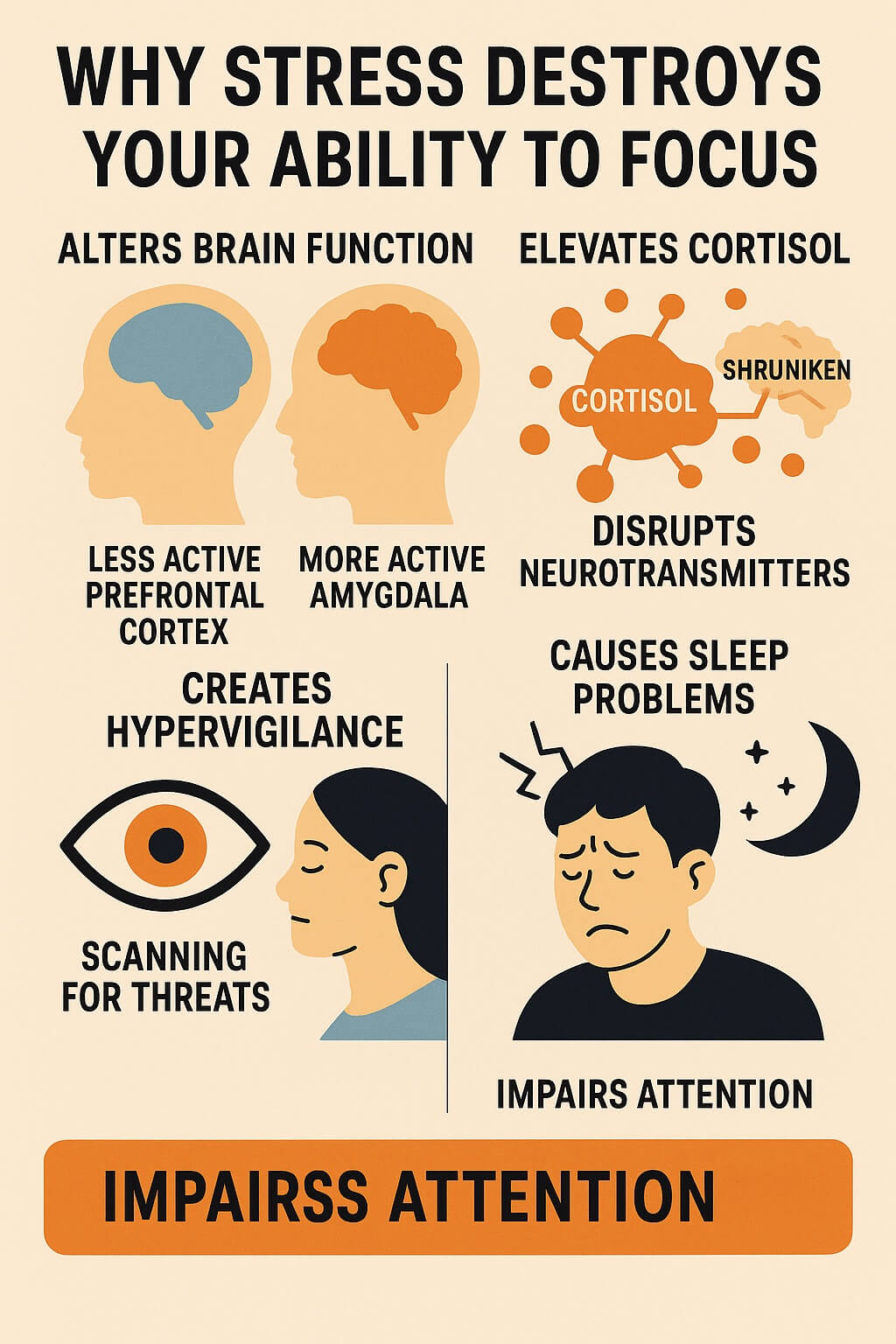

Chronic stress fundamentally alters brain function in ways that directly impair attention and concentration. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functions including sustained attention, working memory, and impulse control, becomes less active under prolonged stress. Meanwhile, the amygdala, your brain’s threat detection center, becomes hyperactive and hypersensitive. This shift prioritizes scanning for danger over deep engagement with any single task.

Cortisol, the primary stress hormone, affects multiple brain regions involved in attention regulation. Elevated cortisol over extended periods actually shrinks the hippocampus, which plays crucial roles in memory formation and retrieval. It also disrupts the balance of neurotransmitters including dopamine and norepinephrine that regulate attention, motivation, and reward processing. Without proper neurotransmitter balance, sustaining focus on activities that don’t provide immediate gratification becomes neurologically difficult rather than just psychologically challenging.

The constant activation of your stress response system creates a state of hypervigilance where your brain continuously scans the environment for threats. This scanning mode is incompatible with the relaxed, open attention required for reading, creative activities, or deep work. Your nervous system interprets stillness and single-focus engagement as potentially dangerous because you’re not monitoring your surroundings. This explains why activities that should be relaxing instead feel uncomfortable or impossible to maintain.

Sleep disruption from chronic stress compounds attention problems significantly. Stress frequently causes insomnia, fragmented sleep, or poor sleep quality even when you spend adequate time in bed. Sleep deprivation impairs attention, working memory, and executive function more dramatically than most people realize. Even mild sleep debt accumulates cognitive deficits that make sustained focus increasingly difficult.

The mental exhaustion following prolonged stress depletes the cognitive resources necessary for effortful attention. Your brain has been running in crisis mode, consuming enormous amounts of energy. The depletion affects your ability to direct and maintain attention voluntarily. Tasks requiring sustained mental effort feel impossible not because you lack motivation but because you lack the neurological fuel to power that effort.

Why can’t you stop checking your phone even when you want to?

Smartphone design exploits fundamental aspects of human psychology and neurobiology to create compelling, habit-forming interactions. The variable reward schedule, where you never know if checking will reveal something interesting, activates the same dopamine pathways that gambling does. Your brain learns to seek these small dopamine hits compulsively, especially when you’re depleted and seeking any form of stimulation or relief.

Phone checking becomes a automatic behavior rather than a conscious choice after sufficient repetition. These automatized behaviors bypass conscious decision-making, happening before you’re even aware you’ve picked up the device. The behavior gets triggered by cues including boredom, stress, transitions between activities, or even just seeing the phone. Breaking these automatic patterns requires more than willpower because the behavior operates below conscious awareness.

Phones provide escape from uncomfortable internal states including anxiety, restlessness, or the mental effort required for sustained attention. When you sit down to read and immediately feel the urge to check your phone, you’re often unconsciously avoiding the discomfort of trying to focus when focusing feels difficult. The phone offers instant relief from that discomfort through distraction and novelty.

The paradox of phone use is that it simultaneously over-stimulates and under-satisfies. The rapid switching between snippets of content, the scroll-based interfaces, and the constant novelty train your brain to expect high stimulation with minimal effort. This makes activities requiring sustained attention on a single focus feel unbearably slow and understimulating by comparison. You’ve essentially trained your attention system to expect and require constant novelty.

Stress amplifies phone checking behavior because the device provides a sense of control and distraction when other aspects of life feel overwhelming. During and after stressful periods, people often increase digital consumption as a coping mechanism. This increase reinforces the habit loops while simultaneously fragmenting attention further, creating a self-perpetuating cycle.

Is it normal to read without actually reading?

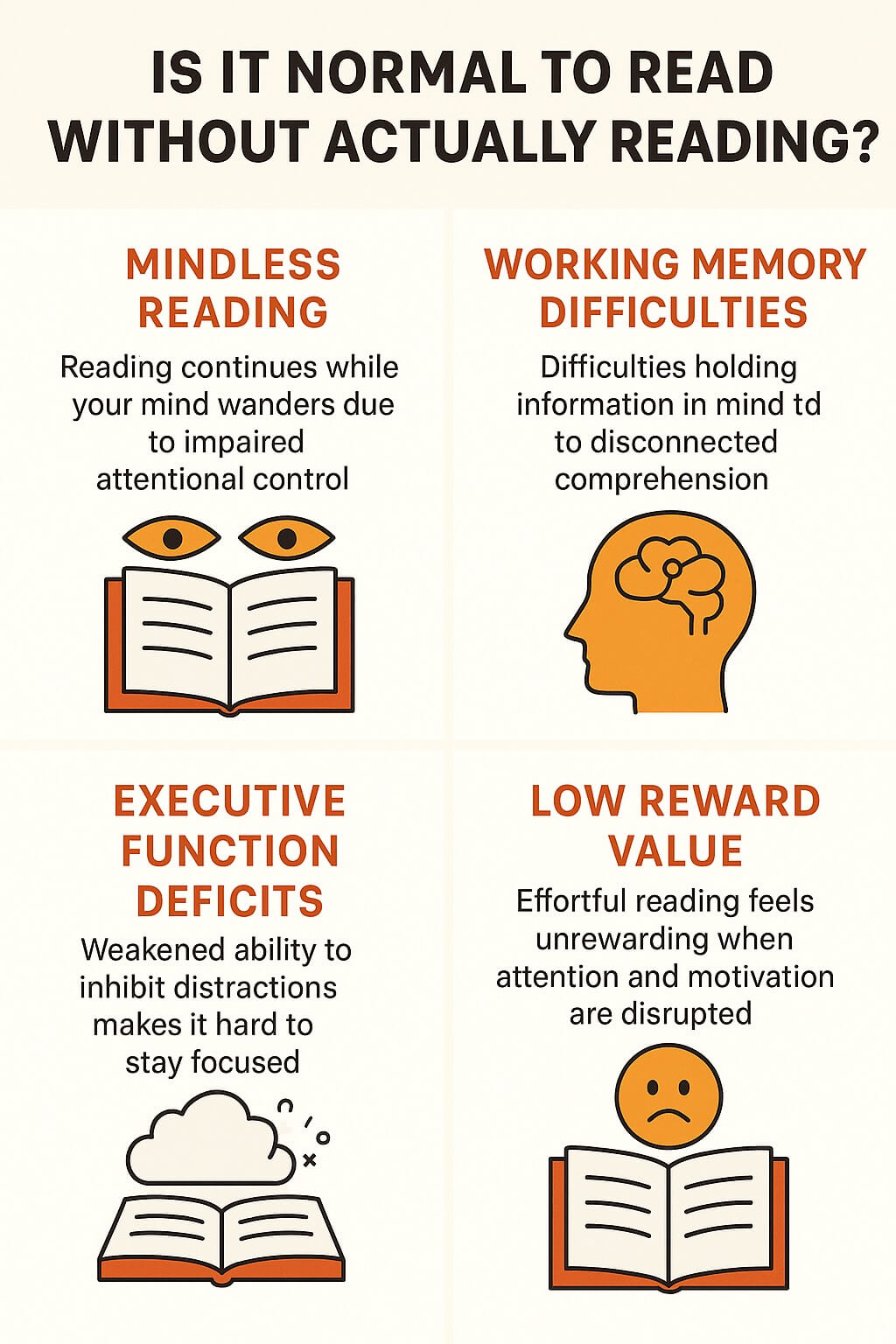

Mind wandering while reading affects everyone occasionally, but chronic stress and attention fragmentation make it constant rather than occasional. This phenomenon, where your eyes track words while your mind occupies itself elsewhere, indicates that your attentional control systems aren’t functioning normally. You’re experiencing what researchers call “mindless reading,” where the mechanical process of eye movement continues without comprehension or encoding.

The working memory impairment from stress directly affects reading comprehension. Working memory holds information temporarily while you process it, allowing you to connect each sentence to previous ones and build coherent understanding. When working memory function degrades, each sentence exists in isolation rather than building on what came before. You finish a paragraph with no idea what it said because the information never properly consolidated.

Reading requires executive function to inhibit distracting thoughts and maintain focus on the text. The executive function deficits from chronic stress mean your brain can’t effectively suppress irrelevant thoughts and maintain directed attention. Your mind drifts to worries, tasks, or random associations because the neural mechanisms that would normally keep you focused on the text aren’t working efficiently.

The effort required to read feels disproportionate to the reward when your attention and motivation systems are disrupted. Your brain has been primed for high stimulation and immediate feedback through phone use and stress-driven urgency. The slow, effortful process of reading and the delayed satisfaction of understanding feels unrewarding by comparison, making it difficult to sustain motivation.

Different types of reading demand different cognitive resources. Difficult or dense material that requires careful attention and integration becomes nearly impossible when your attention system is compromised. Even simple material feels difficult because the basic mechanisms of sustained attention and comprehension aren’t functioning properly. This isn’t about the material being too hard. It’s about your cognitive systems being too depleted.

How long does it take to rebuild attention span?

Attention recovery timelines vary significantly based on how long you’ve been stressed, the severity of your attention impairment, and what interventions you implement. Some improvements often appear within the first week or two of reducing stress and implementing attention-building practices. However, substantial recovery of sustained attention capacity typically requires consistent effort over several months.

The initial improvements usually involve reduced mental restlessness and slightly longer periods of sustained focus. You might extend your reading from one paragraph to several paragraphs, or from five minutes to ten minutes of coloring. These incremental gains feel small but represent genuine neurological changes. The prefrontal cortex begins recovering function, stress hormones normalize, and neurotransmitter balance improves.

Significant attention restoration, where you can sustain focus for extended periods without struggle, often requires three to six months of consistent practice and reduced stress. This timeline reflects the actual neurological changes involved including strengthening neural pathways for sustained attention, normalizing stress response systems, and rebuilding executive function capacity.

Some aspects of attention recover faster than others. The ability to briefly focus when necessary often returns before the capacity for extended, voluntary focus. You might regain decent attention at work where external structure and deadlines provide motivation before you can sustain attention on personally chosen activities like reading for pleasure.

Factors that accelerate recovery include adequate sleep, stress reduction, regular physical activity, mindfulness practice, and deliberate attention training. Conversely, ongoing high stress, poor sleep, excessive screen time, and expecting too much too soon all slow the recovery process. Understanding that rebuilding attention is genuine neurological recovery rather than just “trying harder” helps set realistic expectations.

What’s the best way to start rebuilding focus?

Starting with your current capacity rather than your desired capacity prevents the frustration that derails recovery attempts. If you can only sustain attention for five minutes, make that your starting point rather than forcing yourself to sit for thirty minutes fighting constant distraction. Success builds on small, achievable increments rather than ambitious goals that highlight how far you’ve fallen.

Choosing activities that are genuinely interesting to you makes the effortful work of rebuilding attention more sustainable. If you don’t actually enjoy the book you’re trying to read, your brain has no motivation to overcome the difficulty of sustained focus. Start with content that captures your interest naturally rather than content you think you should engage with. Mystery novels might work better than literary fiction. Graphic novels might provide scaffolding that helps maintain engagement.

Creating external structure supports attention when internal regulation is impaired. Set a timer for a short, manageable period like five or ten minutes. Commit to sustaining attention for just that brief window. The defined endpoint makes the effort feel achievable rather than endless. Gradually increase the duration as your capacity improves, adding just a minute or two at a time.

Reducing competing demands on your attention creates conditions where focus becomes possible. Put your phone in another room, not just on silent nearby. Close unnecessary browser tabs. Create a physical environment with minimal distractions. Your compromised attentional control can’t effectively filter distractions, so removing them externally prevents the need for constant internal battling.

Pairing attention practice with optimal biological conditions improves success rates. Attempt focused activities when you’re most alert rather than exhausted. For many people, this means morning or mid-morning rather than evening. Ensure you’re adequately hydrated and have eaten recently, as both dehydration and low blood sugar impair attention significantly.

Does meditation actually help or is it just trendy advice?

Meditation specifically trains the attentional control networks that chronic stress has compromised. The practice of noticing when your mind wanders and gently returning attention to your breath or chosen focus is literally exercising the same neural circuits involved in all sustained attention. Research consistently shows that regular meditation practice increases gray matter in prefrontal regions and strengthens connectivity in attention networks.

The catch is that meditation feels nearly impossible when your attention is severely fragmented. Sitting still and trying to focus feels uncomfortable, frustrating, and potentially overwhelming. This doesn’t mean meditation won’t help. It means you may need to start with extremely brief sessions and more accessible forms of practice than traditional seated meditation.

Guided meditations provide external structure that supports attention when self-directed focus feels impossible. The voice guides your attention, reducing the burden on your own compromised attentional control. Even if your mind wanders constantly during a ten-minute guided session, the repeated act of noticing the wandering and returning attention provides beneficial training.

Movement-based mindfulness practices including walking meditation or mindful yoga may be more accessible than seated meditation when you’re restless and struggling with focus. These practices engage your body and provide changing sensory input while still training attention, making them easier to sustain than trying to sit motionless.

Starting with just two or three minutes of practice prevents the overwhelm and frustration that makes people abandon meditation entirely. You can absolutely benefit from extremely brief sessions when you’re rebuilding capacity. Consistency matters more than duration. Three minutes daily provides more benefit than ambitious 30-minute sessions you can’t actually sustain.

Why do some activities hold attention better than others?

Activities with clear, immediate feedback engage attention more easily than those with delayed or abstract rewards. Video games, for example, provide constant feedback and reward, making them much easier to focus on than reading. This doesn’t make them better or worse for attention recovery, but it explains why some activities feel possible while others feel impossible.

The level of difficulty relative to your current skill creates flow states that support sustained attention. Activities that are too easy bore you, while activities that are too difficult frustrate you. Either extreme makes sustained focus difficult. Finding activities at the edge of your ability where you’re challenged but capable creates optimal conditions for engagement.

Novel activities activate curiosity and interest that can overcome attention difficulties more easily than familiar activities. While comfort and routine have value, trying something completely new sometimes bypasses the learned pattern of fragmented attention. Your brain approaches novel activities with fresh interest rather than the habitual distraction that accompanies familiar tasks.

Multisensory engagement strengthens attention by involving more brain regions in the activity. Activities that engage visual, tactile, and kinesthetic senses simultaneously often hold attention better than purely cognitive tasks. This explains why hands-on crafts, cooking, or art projects might be more accessible than reading during attention recovery.

Social accountability and external deadlines provide structure that compensates for impaired internal motivation and attention control. Work tasks often remain somewhat manageable despite attention problems because of external consequences and structure. Using this same principle intentionally, like joining a book club or taking a class, creates support for activities you struggle to sustain independently.

Can you rebuild attention while still using your phone?

Complete phone elimination isn’t realistic or necessary for most people, but the way you use your phone significantly impacts attention recovery. The constant checking behavior and passive scrolling actively work against attention rebuilding by reinforcing the habit of fragmented focus. Modifying phone use rather than eliminating it entirely provides a middle path.

Creating friction between impulse and action disrupts automatic checking behaviors. Simple changes like removing apps from your home screen, turning off all notifications, or keeping your phone in a drawer rather than your pocket make checking require deliberate choice rather than unconscious habit. This friction provides the pause necessary for conscious decision-making about whether you actually want to check your phone.

Designated phone-free periods train attention while allowing normal phone use at other times. Even starting with just 30 minutes or an hour of phone-free time daily provides practice sustaining attention without the constant interruption of checking. Gradually extend these periods as your tolerance improves and you notice the benefits of uninterrupted focus.

Changing how you use your phone when you do use it helps break the scroll-and-switch pattern that fragments attention. Choose specific content to engage with rather than scrolling feeds. Read a full article instead of skimming headlines. Watch an entire video instead of constantly seeking the next one. Using your phone deliberately trains sustained focus even during screen time.

Using technology strategically to support attention recovery rather than undermine it shifts the relationship. Apps that block distracting sites during work periods, track screen time to build awareness, or provide timed website access can help. The phone becomes a tool supporting your goals rather than an object of compulsive behavior.

What’s the difference between taking a break and avoiding difficult focus?

Genuine breaks restore capacity, while avoidance depletes it further. This distinction matters enormously for attention recovery but can be difficult to identify in the moment. Genuine breaks feel restorative even if they’re brief. You return to the focused activity with renewed capacity, even if only slightly improved. Avoidance often increases restlessness and makes returning to the focused activity even harder.

The intention behind the break provides one clue. If you consciously decide to take a five-minute break after sustaining focus for your planned duration, that’s a genuine break. If you impulsively reach for distraction because focusing feels uncomfortable, that’s usually avoidance. The conscious choice versus automatic impulse distinguishes between strategic rest and compulsive escape.

What you do during the break affects whether it restores or depletes. Standing up, stretching, looking out a window, or getting a drink of water provides genuine restoration. Checking your phone or scrolling social media typically doesn’t restore attention capacity and often makes returning to focus harder by reactivating the fragmented attention pattern.

The feeling after the break reveals its true nature. Restorative breaks leave you feeling slightly refreshed with marginally improved capacity to focus. Avoidance breaks often leave you feeling guilty, more scattered, and even less capable of focusing than before. Your subjective experience after the break provides important feedback.

Building in planned breaks prevents the need for escape-driven avoidance. Using something like the Pomodoro Technique with structured work periods and break periods creates a rhythm that satisfies the need for mental rest without derailing focus entirely. Knowing a break is coming helps you sustain attention during work periods.

How do you deal with the frustration of having no attention span?

The frustration itself often worsens attention problems by activating stress responses that further impair focus. When you berate yourself for losing focus, your brain interprets that self-criticism as threat, activating the same stress systems that created the attention problem initially. This creates a vicious cycle where frustration about poor attention worsens the attention difficulty.

Reframing attention struggles as injury recovery rather than personal failure changes the emotional tone around the challenge. You wouldn’t berate yourself for not being able to run immediately after breaking your leg. Attention impairment from chronic stress is similarly a real injury requiring recovery time and appropriate treatment. This reframe reduces shame and increases compassion.

Celebrating small wins builds momentum and provides the positive reinforcement your reward system needs. If you sustained attention for seven minutes today compared to five minutes yesterday, that’s genuine progress worth acknowledging. These incremental improvements represent real neurological changes even though they feel insignificant compared to your previous capabilities or desired outcomes.

Comparing yourself to your own progress rather than to others or to your pre-stress self prevents demoralizing comparisons. Other people’s attention capacity isn’t relevant to your recovery. Your own attention from before your stressful period set a baseline you’re working toward but doesn’t define your current worth or ability. The only meaningful comparison is between where you are now and where you were last week.

Accepting that recovery isn’t linear prevents catastrophizing during inevitable setbacks. You’ll have days where attention feels impossible despite recent progress. This doesn’t mean you’ve lost all gains or that recovery isn’t happening. It means recovery involves fluctuation. The overall trend matters more than daily variation.

Does exercise really impact attention or is it just general wellness advice?

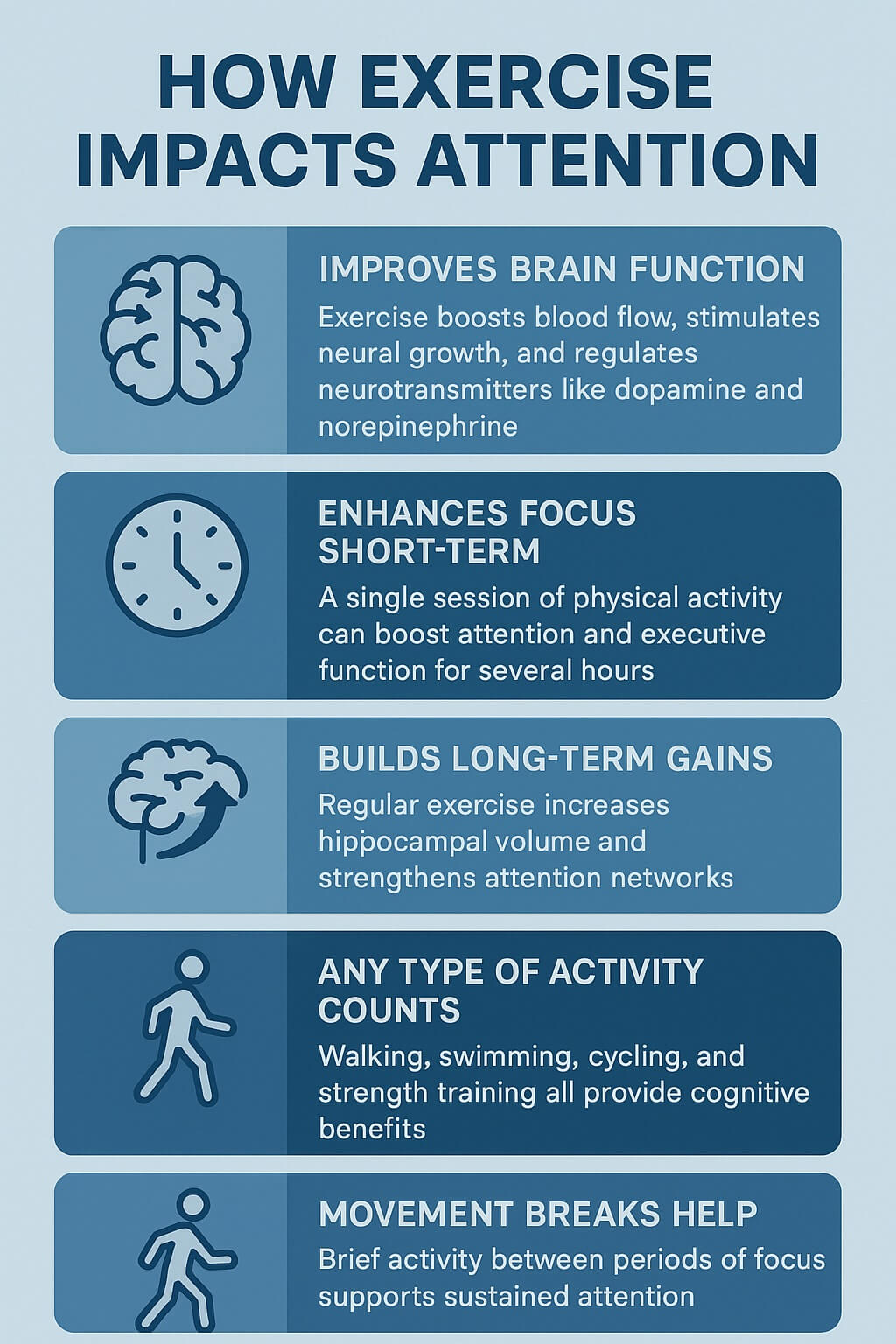

Physical activity directly affects the neurological systems underlying attention through multiple mechanisms. Exercise increases blood flow to the brain, delivering oxygen and nutrients essential for optimal function. It stimulates production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which promotes neural growth and plasticity. It modulates neurotransmitter systems including dopamine and norepinephrine that regulate attention.

The immediate effects of exercise on attention are well-documented. Even a single session of moderate physical activity improves attention, working memory, and executive function for several hours afterward. This means strategic exercise timing can create windows of improved focus for activities requiring sustained attention. Morning exercise might support better work focus throughout the day.

The long-term effects of regular exercise include structural brain changes that support better attention regulation. Consistent physical activity increases hippocampal volume, strengthens prefrontal cortex function, and improves connectivity in attention networks. These aren’t just temporary boosts. They’re actual neurological adaptations that improve baseline attentional capacity.

The type and intensity of exercise matter less than consistency and doing something you’ll actually maintain. Walking provides cognitive benefits. So does swimming, dancing, cycling, or strength training. High-intensity exercise isn’t necessary for brain benefits. Moderate activity sustained over time works well for most people.

Movement breaks during focused work sessions serve double duty by providing both physical activity and mental rest. Standing up and moving for even five minutes between focus periods helps maintain attention across longer sessions. The movement provides the neurological benefits of exercise while the change of activity offers mental restoration.

What if you can’t achieve anything and feel like a failure?

Achievement orientation actually interferes with attention recovery when you measure success by output rather than by the process of practicing attention. Focusing on what you produce creates pressure that activates stress responses undermining the attention you’re trying to rebuild. Shifting focus to the practice itself rather than the outcome reduces this pressure.

Redefining achievement for this recovery period acknowledges that sustaining attention for even brief periods represents significant accomplishment given your current neurological state. Successfully sitting with a coloring book for five minutes without giving up is a genuine achievement. Reading three pages with comprehension is an achievement. These aren’t failures because they don’t match your previous capacity. They’re successes because they represent progress from where you currently are.

The feelings of failure often stem from comparing your current diminished capacity to your memories of previous ability or your expectations of where you think you should be. This comparison is both unfair and counterproductive. You’re recovering from genuine neurological changes caused by chronic stress. Expecting yourself to perform at pre-injury levels during recovery sets you up for constant disappointment.

Practicing self-compassion doesn’t mean lowering standards or accepting permanent limitation. It means treating yourself with the kindness and patience you’d show someone else recovering from injury. This compassionate approach actually supports better recovery than harsh self-criticism, which maintains the stress that caused the attention impairment initially.

Finding meaning in the recovery process itself rather than only valuing the end result makes the journey sustainable. The practice of rebuilding attention teaches patience, self-awareness, and self-compassion. These skills have value beyond just restoring your focus. The process of recovery can actually develop capabilities you didn’t have before if you engage with it thoughtfully rather than just fighting to get back to your previous state.

Is there a connection between attention problems and anxiety?

Anxiety and attention problems maintain each other in a self-reinforcing cycle. Anxiety activates threat-detection systems that prioritize vigilance over sustained focus. This makes concentration difficult, which creates more anxiety about your inability to focus, which further impairs attention. Breaking this cycle requires addressing both the anxiety and the attention difficulty simultaneously.

The constant mental chatter and worry characteristic of anxiety directly competes with the mental space required for sustained attention. When your mind fills with anxious thoughts about the future or ruminations about the past, there’s no capacity remaining for present-focused attention on the task at hand. The anxious thoughts aren’t willful distraction. They’re intrusive and compelling, hijacking attention automatically.

Attention difficulties can generate secondary anxiety even when anxiety wasn’t your primary problem initially. Noticing that you can’t focus the way you used to creates worry about cognitive decline, job performance, or permanent damage. This anxiety about attention problems then worsens the attention difficulties, creating a cycle that didn’t exist originally.

Treating the attention problem often reduces anxiety symptoms because improved focus creates a sense of control and capability. Successfully sustaining attention for increasing periods proves to yourself that your cognitive abilities aren’t permanently broken. This reduces the anxiety that arises from feeling mentally impaired and out of control.

Conversely, addressing anxiety through therapy, stress management, or medication often improves attention as a secondary benefit. As the anxiety resolves and threat-detection systems downregulate, cognitive resources become available for sustained attention. This is why comprehensive approaches addressing both attention and emotional regulation work better than trying to force attention improvement through willpower alone.

Can diet or supplements improve attention span?

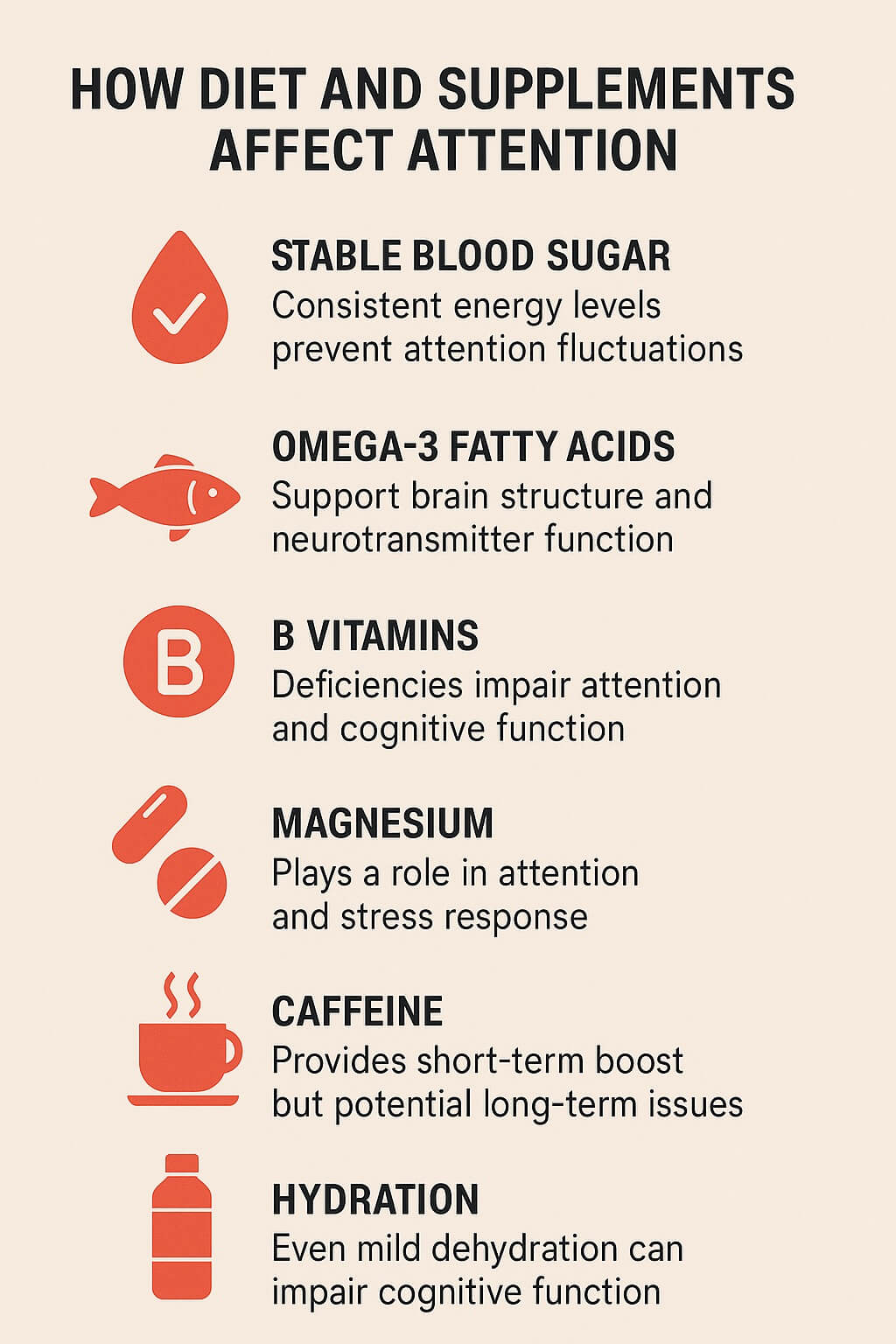

Nutrition affects brain function and attention through multiple pathways, though no single food or supplement magically fixes attention problems. Stable blood sugar supports steady attention by providing consistent fuel for brain function. Large blood sugar swings from refined carbohydrates and inadequate protein create attention fluctuations that worsen existing difficulties.

Omega-3 fatty acids, particularly DHA, support brain structure and function including attention regulation. These essential fats concentrate in brain cell membranes and influence neurotransmitter signaling. While supplementation won’t immediately fix attention problems, ensuring adequate intake supports the neurological recovery underlying attention improvement.

B vitamins, particularly B6, B9, and B12, play crucial roles in neurotransmitter production and nervous system function. Deficiencies in these vitamins impair attention, mood, and cognitive function. However, supplementation only helps if you’re deficient. Taking extra B vitamins beyond adequate levels doesn’t typically provide additional attention benefits.

Magnesium deficiency affects attention and anxiety, and many people don’t consume enough through diet. This mineral supports hundreds of enzymatic processes including neurotransmitter function and stress response regulation. Supplementation may help if you’re deficient, though testing can determine whether this is relevant for you.

Caffeine provides temporary attention enhancement but can worsen attention problems long-term if used habitually in high doses. Moderate caffeine use might support focus during critical periods, but dependence creates attention difficulties when caffeine wears off or when you’re trying to reduce consumption. The crash after caffeine creates worse attention deficits than existed before consumption.

Hydration affects attention more than most people realize. Even mild dehydration impairs cognitive function including attention and working memory. Drinking adequate water throughout the day provides basic support for brain function without any downsides or complications.

What role does sleep play in recovering attention?

Sleep problems and attention problems interact bidirectionally, with each worsening the other. Poor sleep directly impairs the prefrontal cortex functions underlying sustained attention, working memory, and executive control. Even one night of inadequate sleep measurably reduces attention capacity. Chronic sleep deprivation creates attention deficits that are indistinguishable from those caused by stress.

The quality of sleep matters as much as duration. Fragmented sleep that prevents sufficient time in deep and REM stages impairs memory consolidation and attention even if you spend adequate hours in bed. Stress often disrupts sleep architecture, reducing restorative sleep stages while increasing light sleep and nighttime waking.

The glymphatic system clears metabolic waste from the brain during sleep, with peak clearing during deep sleep stages. Inadequate or poor-quality sleep prevents efficient waste clearance, leaving your brain operating in a fog of accumulated metabolic byproducts. This physiological reality explains why poor sleep leaves you feeling mentally cloudy and unable to focus.

Prioritizing sleep improvement often provides more benefit for attention recovery than any other single intervention. Even modest sleep improvements frequently produce noticeable attention benefits within days. Conversely, attempting to rebuild attention while chronically sleep-deprived rarely succeeds because you’re working against powerful physiological limitations.

Sleep hygiene modifications including consistent bed and wake times, reducing evening screen exposure, keeping the bedroom cool and dark, and avoiding caffeine after early afternoon all support better sleep. These aren’t just general wellness suggestions. For attention recovery specifically, sleep optimization may be the most important intervention you can implement.

How do you know if your attention is actually improving?

Tracking progress feels difficult when changes are gradual and subjective. Keeping a simple log of your attention practice provides concrete evidence of improvement that your subjective experience might miss. Note how long you sustained focus each day and what you were able to accomplish. Reviewing this log weekly or monthly reveals progress patterns that daily variation obscures.

Noticing increased time between phone checks indicates improving attention control. If you previously checked your phone every few minutes and now go 15 or 20 minutes between checks, that’s measurable progress even if it doesn’t feel significant in the moment. Reduced checking frequency reflects genuine improvement in impulse control and sustained attention.

Completing reading or activities that were previously impossible demonstrates concrete progress. If you finish an entire magazine article or color an entire page without giving up, that represents real improvement from when you couldn’t sustain focus for more than a paragraph or five minutes. These completions matter more than the amount of time they take.

Reduced mental restlessness during focused activities indicates recovering attention regulation. If sitting with a book feels less uncomfortable and you notice fewer intrusive urges to switch activities, your nervous system is downregulating and your attention control is improving. This subjective shift often precedes measurable increases in sustained focus duration.

Improved work performance or productivity often appears before you notice changes in voluntary attention during leisure activities. If you notice you’re completing work tasks more efficiently or with less struggle, your attention is recovering even if reading for pleasure still feels difficult. Work attention often recovers first because of external structure and consequences.

What’s the role of boredom tolerance in attention recovery?

Modern life has conditioned many people to fear and avoid boredom through constant stimulation. However, boredom tolerance is actually essential for sustained attention. Activities that require sustained focus inevitably include periods of boredom where novelty decreases and effort continues. Without tolerance for this discomfort, you’ll constantly seek new stimulation rather than sustaining attention.

Rebuilding boredom tolerance means sitting with uncomfortable feelings of restlessness, understimulation, or impatience without immediately seeking distraction. This practice isn’t about suffering needlessly. It’s about developing capacity to persist through temporary discomfort toward meaningful goals. The inability to tolerate brief boredom fragments attention across any activity that isn’t instantly engaging.

Technology companies have weaponized boredom intolerance by designing products that provide constant novelty and stimulation. Your brain has learned to expect and require this stimulation level. Relearning that boredom is a normal, survivable human experience rather than an emergency requiring immediate remedy rebuilds the foundation for sustained attention.

Deliberately practicing low-stimulation activities builds boredom tolerance gradually. This might mean sitting quietly for a few minutes without any activity, taking a walk without headphones, or engaging with simple, repetitive activities. These practices feel uncomfortable initially but develop the capacity to sustain attention even when something isn’t maximally engaging every moment.

Understanding that meaningful activities inevitably include boring components makes boredom tolerance feel purposeful rather than pointless. Reading a book includes boring paragraphs. Learning skills includes tedious practice. Creative projects include repetitive technical work. The ability to persist through these low-stimulation phases determines whether you can complete anything substantial or whether you’ll constantly switch to new activities that seem more interesting.