There’s something weirdly satisfying about finding a skincare trick that seems to work faster than anything else you’ve tried. When you discover that slathering petroleum-based ointment on a whitehead makes it come off easily after an hour, it feels like you’ve unlocked a secret. The whitehead wipes away clean, and you’re left feeling like you’ve won the battle against your skin.

But then you look closer and see a raw spot where the whitehead used to be. It looks like a tiny crater, and suddenly you’re wondering if this quick fix is actually creating a bigger problem. If you’re already dealing with acne scars, the last thing you want is to make things worse with a technique that seems helpful in the moment but damaging in the long run.

Let’s talk about what’s actually happening when you use occlusive ointments on whiteheads, whether this method increases scarring risk, and what dermatologists would say about this whole approach.

What actually happens when you put occlusive ointment on a whitehead?

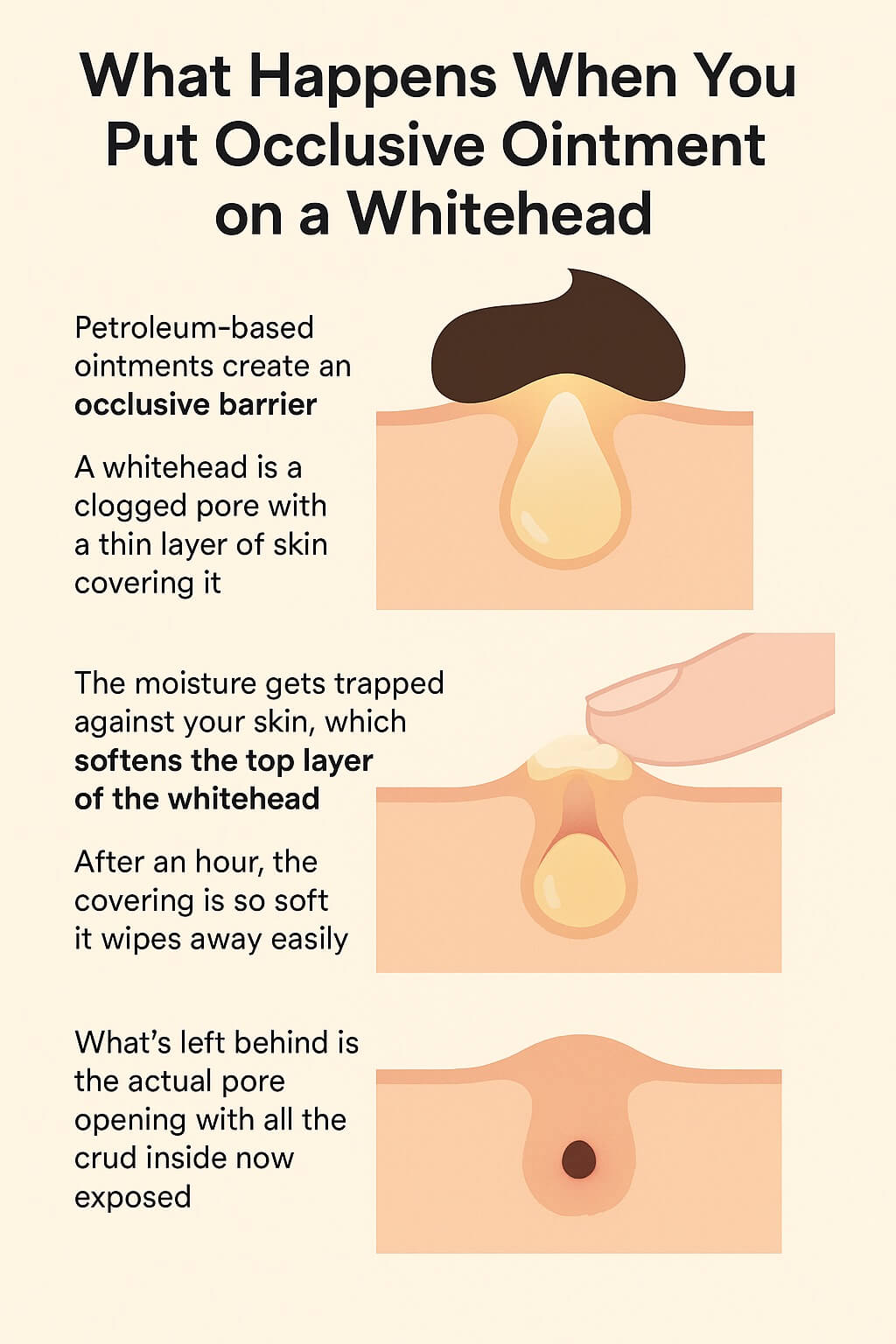

Petroleum-based ointments create what’s called an occlusive barrier. This means they seal moisture against your skin and don’t let anything in or out. When you put a thick layer over a whitehead, you’re essentially creating a humid, sealed environment.

The moisture gets trapped against your skin, which softens everything—including the top layer of your whitehead. The technical term for this is maceration, which is what happens to your fingers when they get wrinkly after a long bath. Your skin absorbs water and the outer layer becomes soft and weak.

A whitehead is basically a clogged pore with a thin layer of skin covering it. The white part you see is a mixture of dead skin cells, oil, and bacteria trapped under that thin skin layer. When you create that moist, sealed environment with ointment, that thin covering softens significantly.

After an hour of this treatment, the covering has become so soft and fragile that it wipes away easily when you remove the ointment. That’s why the whole whitehead seems to come off so cleanly—you’re not really extracting it the way you would by squeezing. You’re dissolving the thin skin barrier that was holding everything in.

What’s left behind is the actual pore opening with all the crud that was inside now exposed. Sometimes some of it comes away with the ointment, but often there’s still material deeper in the pore. That’s why you’re seeing what looks like a hole or raw spot.

Is this method actually causing the whitehead to heal faster?

Not exactly. What you’re doing is accelerating the process of the whitehead opening, but that’s different from healing. In fact, you might be interrupting the natural healing process your skin was working on.

When your body creates a whitehead, it’s actually trying to push infected material to the surface and out of your skin. The thin layer of skin over the whitehead serves a purpose—it’s protecting the inflamed area underneath while your immune system works to clear out the infection.

Left alone, that whitehead would eventually open on its own or gradually reabsorb. Your skin knows what it’s doing. By artificially softening and removing that protective layer, you’re exposing the wound before your body is ready.

Think of it like picking a scab. The scab is there to protect healing skin underneath. If you pick it off before the skin underneath is ready, you reveal raw, unhealed tissue. That’s essentially what’s happening when you use the ointment method to remove whiteheads.

The satisfaction of seeing the whitehead gone quickly doesn’t mean it’s actually healing faster. You’ve just removed the visible part while potentially leaving the actual infection or inflammation still present deeper in the skin.

Does removing whiteheads this way increase scarring risk?

Yes, this method likely does increase your risk of scarring, and here’s why. Acne scars form when there’s damage to the deeper layers of skin, particularly the dermis. Inflammation from acne triggers changes in how your skin produces collagen during healing. Too much collagen creates raised scars, while too little creates depressed scars or pitting.

When you prematurely remove the protective layer over a whitehead, you’re creating an open wound before the inflammation underneath has resolved. This exposed area is more vulnerable to additional trauma, infection, and deeper inflammation—all things that increase scarring risk.

The “hole” you’re seeing after removing the whitehead is essentially an open pore with inflamed tissue around it and possibly inside it. This wound now has to heal from the outside in, which takes longer and increases the chance of abnormal collagen formation that leads to scarring.

Dermatologists consistently warn against manual extraction at home for this exact reason. Even when they do extractions in their offices, they’re extremely careful about technique, timing, and aftercare. They only extract when the whitehead is truly ready to come out with minimal trauma.

Your ointment method bypasses all those careful considerations. You’re forcing the whitehead open based on convenience and timing rather than whether it’s actually ready. Each time you do this, you’re rolling the dice on whether that particular spot will heal normally or leave a mark.

If you already have acne scars, your skin has shown that it’s prone to scarring. This means you need to be even more careful about how you handle active breakouts. Every additional trauma to your skin increases the likelihood of adding to your existing scar collection.

What about the exposed area after the whitehead comes off?

The raw spot left behind after using the ointment method is particularly problematic. This exposed area is essentially an open wound, and how you treat it in the hours and days following makes a huge difference in outcomes.

The exposed pore and surrounding tissue are vulnerable to bacterial infection. Even though you removed visible pus, bacteria can still be present. Touching the area with your fingers, applying makeup, or exposing it to dirty surfaces increases infection risk.

The wound needs to stay moist to heal properly, but not the kind of sealed moisture that petroleum ointment creates. Wound healing research shows that maintaining appropriate moisture helps skin regenerate better and reduces scarring. However, creating an overly occlusive environment can trap bacteria and cause problems.

Sun exposure on this fresh wound is extremely damaging. UV radiation can cause post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, which means dark marks that last for months or even years. Even if you don’t develop a textured scar, you might get discoloration that’s just as frustrating.

The temptation to keep messing with the area is high. Once you’ve opened that whitehead, you can see into the pore, and you might notice there’s still stuff in there. This leads to more picking, squeezing, and trauma that compounds the damage.

Why does this method feel so effective if it’s actually problematic?

Human psychology plays a big role here. We’re drawn to immediate, visible results. Watching a whitehead disappear in an hour gives you instant gratification that waiting days for natural healing doesn’t provide.

There’s also a strong emotional component to having visible acne. When you have a whitehead, you’re hyper-aware of it. You feel like everyone is staring at it. The urge to make it disappear as fast as possible is overwhelming, even if the rational part of your brain knows you should leave it alone.

The method does work in the sense that it makes the visible whitehead go away quickly. What happens afterward—the slower healing, the increased scarring risk, the potential for more inflammation—is less visible and takes longer to manifest. It’s easy to ignore future consequences when you’re getting immediate relief from the stress of having a visible blemish.

Social media and skincare communities sometimes share these kinds of “hacks” without discussing the downsides. When you see other people having success with a method, it validates your own experience and makes the technique seem safer than it might actually be.

What do dermatologists actually recommend for dealing with whiteheads?

The professional advice is probably not what you want to hear, but it’s important. Dermatologists generally recommend leaving whiteheads alone to heal on their own whenever possible. Your skin has mechanisms for dealing with these issues that work best without interference.

If you absolutely must do something, warm compresses are the safest intervention. Applying a clean, warm washcloth to the area for a few minutes several times a day can help bring the whitehead to the surface naturally and reduce inflammation. This works with your skin’s processes rather than against them.

Spot treatments with benzoyl peroxide or salicylic acid can help reduce bacteria and inflammation while the whitehead heals. These ingredients work over several days rather than hours, but they address the actual problem rather than just removing the visible symptom.

Hydrocolloid patches have become popular for a good reason. These patches absorb fluid from the whitehead and protect the area from touching and bacteria. They work best on whiteheads that have already opened naturally. Unlike the ointment method, they don’t force anything open prematurely.

For persistent or severe acne, prescription treatments like topical retinoids or oral medications address the underlying causes. These prevent new whiteheads from forming in the first place, which is more effective than constantly dealing with individual blemishes as they appear.

Professional extractions done by a dermatologist or trained esthetician are an option for stubborn whiteheads. They use proper technique and sterile tools, and they only extract when the whitehead is truly ready. This minimizes trauma and scarring risk in a way home methods cannot match.

Can I use occlusive ointments for acne treatment without forcing extractions?

There’s actually a legitimate use for petroleum-based ointments in acne care, but it’s different from what you’re doing. The concept is called “slugging” and it involves applying ointment as the final step in your nighttime skincare routine to seal in other products and prevent moisture loss.

Some people find that using ointment over their acne treatments helps reduce irritation from strong active ingredients like retinoids or benzoyl peroxide. The ointment doesn’t treat the acne itself, but it can make your skin more comfortable while you’re using treatments that might otherwise be too harsh.

However, using heavy ointments on active, inflamed acne can potentially make things worse for some people. The occlusive nature can trap bacteria and oil, leading to more clogging. Whether this helps or hurts depends on your specific skin type and the nature of your acne.

The key difference is using ointment as a protective layer versus using it as a tool to force whiteheads open. One is about supporting your skin barrier while using treatments. The other is about actively disrupting your skin’s natural healing process.

What should I do instead when I have an urgent need to deal with a whitehead?

Sometimes you have a big event and a whitehead in an unfortunate location. While the best advice is still to leave it alone, dermatologists recognize that people will try to do something regardless. Here’s the least harmful approach.

If the whitehead is raised and has a very obvious white center that looks ready to burst, you can use a sterile lancet to make the tiniest possible opening. This is much better than forcing it open with pressure or chemicals. The lancet creates a controlled opening rather than tearing the skin.

After making that tiny opening, use a warm compress to gently encourage the contents to drain. Don’t squeeze or press hard. The material should come out easily if it’s actually ready. If it doesn’t come out with gentle pressure, it’s not ready and you should stop.

Immediately after, apply an antibiotic ointment to reduce infection risk, then cover with a hydrocolloid patch. This protects the area and absorbs any remaining fluid. Leave the patch on for several hours or overnight.

For the next few days, keep the area clean and moisturized. Use a gentle cleanser and apply a simple moisturizer. Avoid makeup on the spot if possible, and absolutely use sunscreen to prevent hyperpigmentation.

Accept that even with the most careful technique, you’re still at higher risk for scarring than if you’d left it completely alone. This should be a last resort for special occasions, not your regular approach to every whitehead.

How can I reduce scarring from whiteheads I’ve already treated this way?

If you’ve been using the ointment method regularly and you’re worried about the scarring consequences, there are steps you can take to help your skin heal better going forward.

Stop using the method immediately. Give your skin a chance to heal properly from any current wounds before you cause any new ones. This is hard when you’re used to the instant gratification, but it’s essential.

Use a gentle skincare routine that supports healing. This means a mild cleanser, a good moisturizer, and sunscreen every single day. Skip harsh scrubs or strong active ingredients until any current wounds have fully healed.

Once your skin has healed completely from any recent whitehead incidents, you can consider adding ingredients that help with scarring. Retinoids promote cell turnover and can gradually improve the appearance of scars over months of consistent use. Vitamin C serums help with discoloration and support collagen production.

For existing scars, professional treatments like chemical peels, microneedling, or laser therapy might be necessary. These should be done by qualified professionals who can assess your specific scarring and recommend appropriate treatments.

The most important thing is preventing future scarring by changing how you handle new whiteheads. Every whitehead you leave alone or treat gently is one that won’t add to your scar collection.

The urge to make visible acne disappear instantly is completely understandable, but the ointment method of softening and removing whiteheads is likely doing more harm than good, especially if you’re already prone to scarring. The temporary satisfaction isn’t worth the permanent marks you might be creating.