You made the switch to a pescatarian or plant-based diet with good intentions, but now you’re dragging through workouts that used to feel easy and struggling to find energy for basic daily activities. Your running performance has plummeted, you’re exhausted after exercise that barely used to register as difficult, and even walking your dogs feels like a monumental task. Meanwhile, you’re eating what seems like enough food and trying to do everything right, but your body is clearly telling you something isn’t working.

This situation is incredibly common when people transition from eating meat to plant-based diets, especially athletes or active individuals. The problem usually isn’t plant-based eating itself, but rather how the transition is managed. Understanding what your body needs and how to properly fuel a plant-based active lifestyle can help you regain your energy and performance.

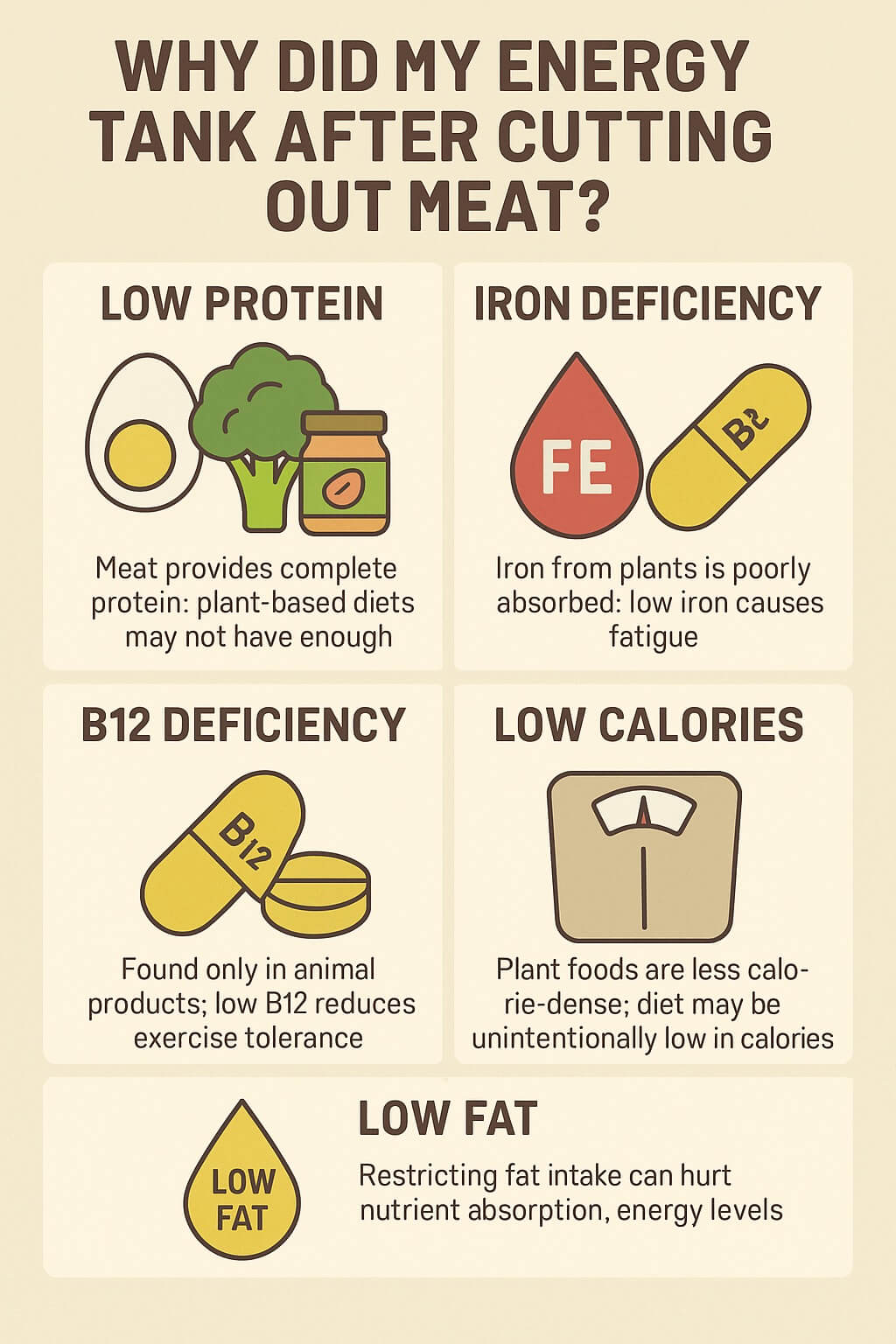

Why did my energy tank after cutting out meat?

When you remove meat from your diet, you’re not just eliminating one food—you’re removing a dense source of easily absorbed protein, iron, B vitamins, creatine, carnitine, and other nutrients that support energy production and athletic performance. If you don’t intentionally replace these nutrients from plant sources, your body starts running on empty even if you’re eating enough calories.

Protein intake often drops significantly when people go plant-based without planning carefully. Meat provides complete proteins with all essential amino acids in forms your body absorbs easily. Plant proteins are often incomplete, lower in certain amino acids, and less bioavailable. If you’re mainly eating eggs, vegetables, and small amounts of nuts and nut butter, you’re likely not getting nearly enough protein to support your activity level.

Iron deficiency is one of the most common causes of fatigue in people who stop eating red meat. Plant-based iron (non-heme iron) is much less efficiently absorbed than the iron in meat (heme iron). Women, athletes, and people who menstruate are particularly vulnerable to iron deficiency when switching to plant-based diets. Low iron means your blood can’t carry enough oxygen to your muscles, causing that dead-tired feeling during and after exercise.

Vitamin B12 only comes from animal products, and deficiency develops gradually over months or years after you stop eating meat. B12 is crucial for energy production, red blood cell formation, and nervous system function. Early deficiency symptoms include fatigue, weakness, and reduced exercise tolerance—exactly what you’re experiencing.

Your overall calorie intake might actually be lower than you think, even if it seems like you’re eating enough. Plant foods are generally less calorie-dense than animal products. A chicken breast has more calories in a smaller volume than the equivalent amount of vegetables. If you’re eating what looks like the same volume of food but it’s mostly vegetables, you’re probably in an unintentional calorie deficit.

Fat intake is another common issue. You mentioned keeping fats around twenty to thirty grams, which is quite low for someone who’s active. Dietary fat is essential for hormone production, nutrient absorption, and sustained energy. Restricting fat too much can tank your energy levels and athletic performance, especially for endurance activities.

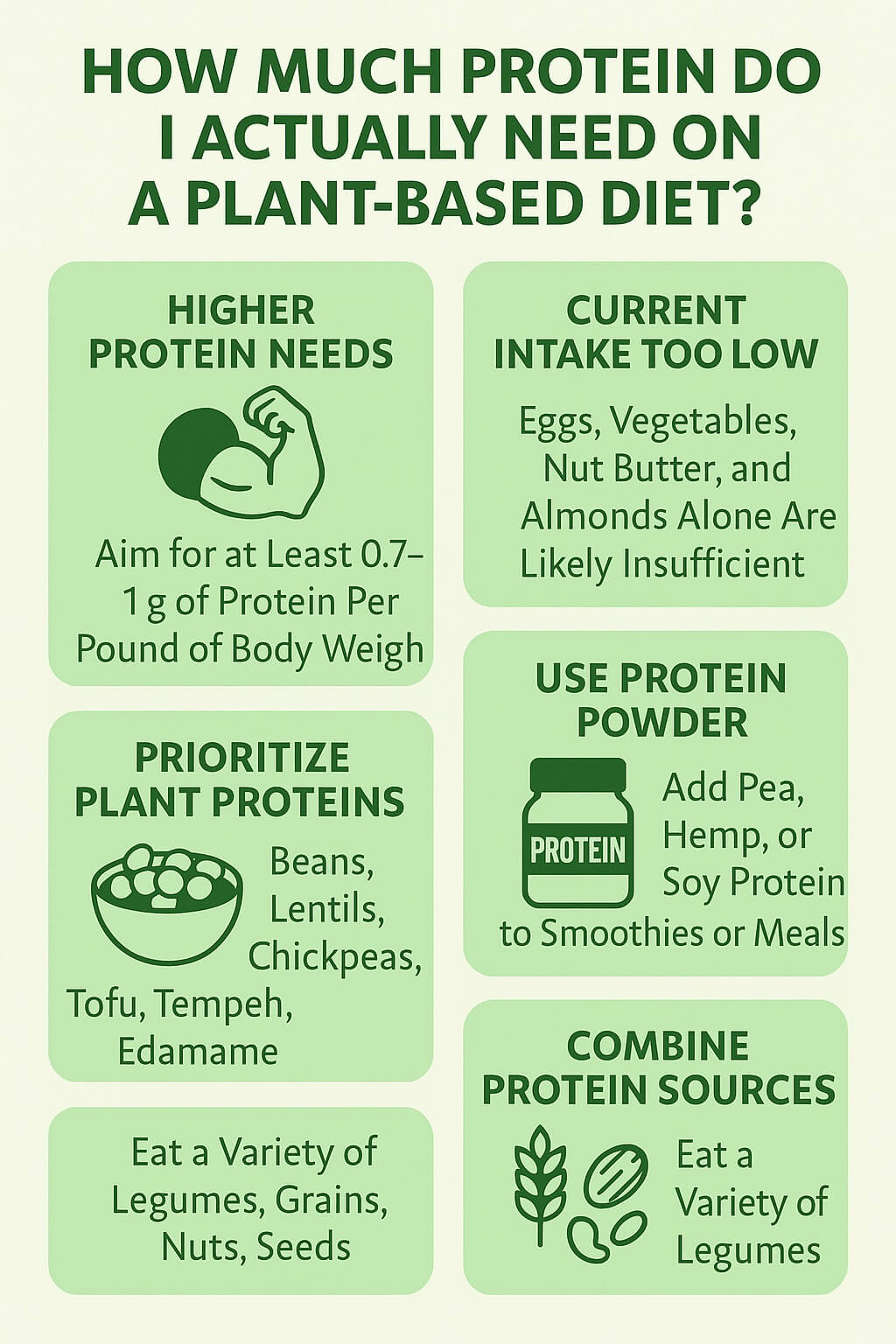

How much protein do I actually need on a plant-based diet?

Active individuals need significantly more protein than sedentary people, and plant-based athletes need even more than omnivorous athletes because plant proteins are less efficiently used by the body. If you’re running and doing high-intensity exercise regularly, you should aim for at least 0.7 to 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight, and possibly more during heavy training periods.

Looking at your current diet of eggs, vegetables, nut butter, and almonds, you’re probably falling far short of this target. One egg contains about six grams of protein. Even if you’re eating three or four eggs daily, that’s only eighteen to twenty-four grams. A couple tablespoons of peanut butter adds another eight grams. A quarter cup of almonds gives you about six grams. You’d need to be eating a lot of these foods to reach adequate protein intake.

Adding fish to your diet several times per week would dramatically increase your protein intake. A serving of fish provides twenty to thirty grams of high-quality protein. If you’re trying to maintain a pescatarian approach, making fish a regular part of your meals rather than an occasional addition would help significantly.

Plant-based protein sources need to be prioritized at every meal. Beans, lentils, chickpeas, tofu, tempeh, edamame, and quinoa all provide substantial protein. A cup of cooked lentils has about eighteen grams of protein. A serving of firm tofu provides about twenty grams. These foods need to become staples rather than occasional additions.

Protein powder becomes almost essential for active people eating plant-based diets. A scoop of pea, hemp, or soy protein powder added to smoothies, oatmeal, or even stirred into soup can add fifteen to twenty-five grams of protein with minimal volume or preparation. This isn’t cheating or taking shortcuts—it’s practical nutrition for athletic performance.

Combining different plant proteins throughout the day ensures you’re getting all essential amino acids. While you don’t need to combine them in every meal like older nutrition advice suggested, eating a variety of protein sources—legumes, grains, nuts, seeds—across the day helps your body access all the amino acids it needs for muscle repair and energy production.

What should I eat before and after workouts?

Your pre-workout nutrition needs more carbohydrates than what you’re currently eating. Sweet potatoes are great, but you need easily digestible carbs closer to your workout time. Rice cakes with nut butter work well, but you might need more carbohydrates than just a couple rice cakes can provide. Consider adding fruit like bananas, which provide quick energy along with potassium.

Timing matters significantly when you’re training hard. Eating a substantial meal three to four hours before exercise gives you sustained energy, while a smaller carb-focused snack thirty to sixty minutes before provides immediate fuel. If you’re running after incline walking without adequate fuel, you’re essentially asking your body to perform on empty tanks.

Post-workout nutrition is crucial for recovery and preventing that dead-tired feeling that lasts all day. You need both protein and carbohydrates within thirty to sixty minutes after intense exercise. The protein supports muscle repair while carbohydrates replenish glycogen stores and help protein absorption. A smoothie with protein powder, fruit, and perhaps some oats hits these needs efficiently.

Your current diet seems very low in quick-digesting carbohydrates. While vegetables are nutritious, they don’t provide the concentrated energy your muscles need for high-intensity exercise. Adding more grains, starchy vegetables, and fruit around your workouts would likely improve your energy significantly.

Fat intake before intense exercise should be moderate because fat slows digestion. Save higher-fat foods like nuts and nut butter for meals further from your workout times. Before running or high-intensity training, focus on easily digestible carbs with moderate protein and minimal fat.

Consider whether you’re eating enough overall around your training. Athletes often need to eat more frequently when switching to plant-based diets because the foods are less calorie-dense. If you’re only eating three meals daily, adding snacks or even a fourth small meal might be necessary to support your activity level.

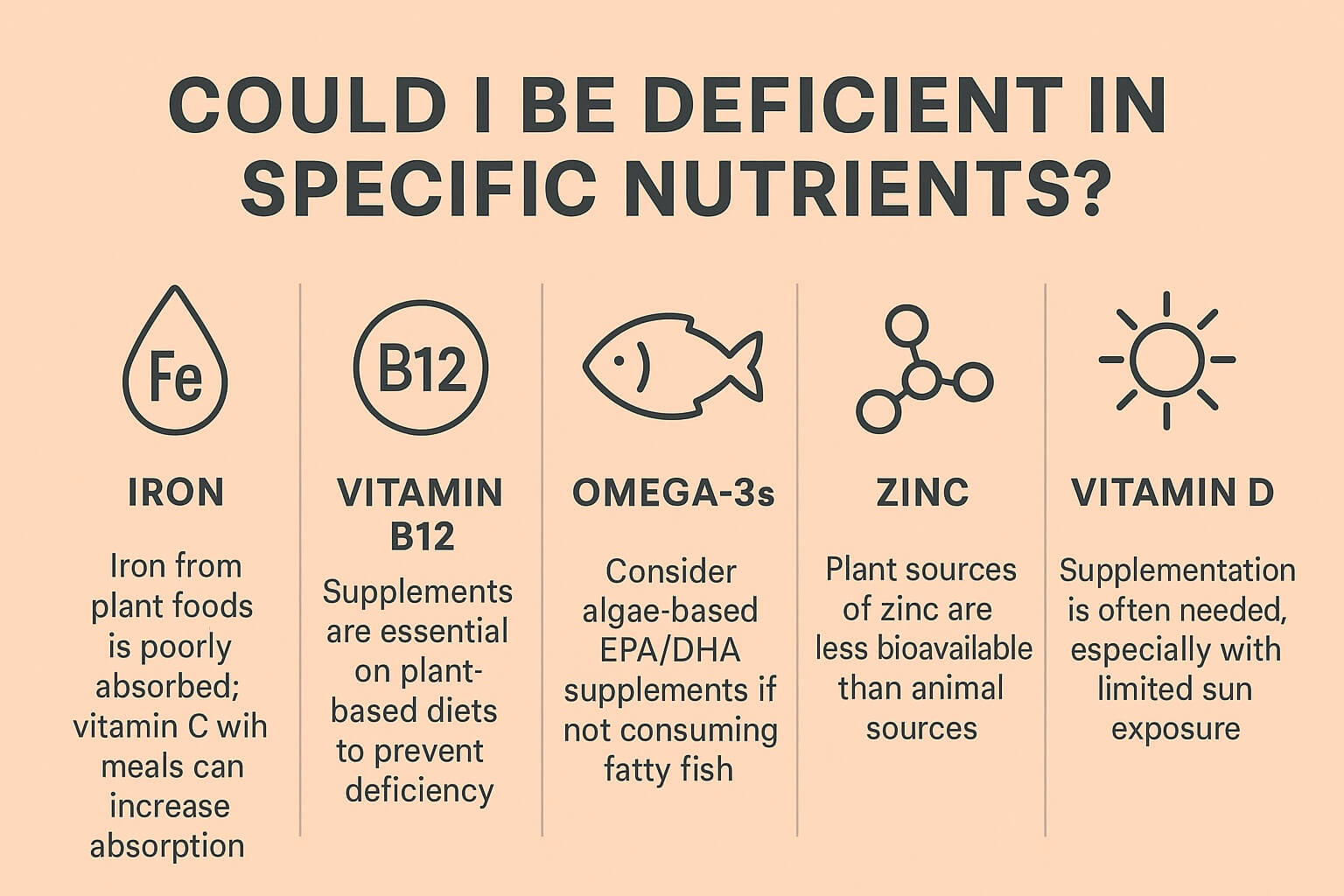

Could I be deficient in specific nutrients?

Iron deficiency is extremely likely given your symptoms and dietary pattern. Eggs contain some iron, but not nearly as much as red meat. Vegetables contain iron, but the non-heme iron from plants is absorbed at much lower rates than heme iron from meat. Fatigue during exercise, feeling wiped out afterward, and general low energy are classic iron deficiency symptoms.

To improve iron absorption from plant foods, combine them with vitamin C sources. Eating tomatoes, peppers, citrus fruits, or strawberries with iron-rich foods significantly increases absorption. Cook in cast iron pans when possible, as this actually adds iron to your food. Avoid tea and coffee with meals, as these inhibit iron absorption.

Vitamin B12 supplementation is non-negotiable for anyone eating a primarily plant-based diet. Even pescatarians who eat fish regularly might not get adequate B12, especially if they’re not eating fish daily. Take a B12 supplement providing at least 250 micrograms daily, or 2500 micrograms weekly. This isn’t optional—it’s essential for preventing serious deficiency.

Omega-3 fatty acids, particularly EPA and DHA, are harder to get on plant-based diets. While flax and chia seeds provide ALA omega-3s, your body converts only a small percentage to the EPA and DHA your brain and body need. If you’re eating fish, prioritize fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, or sardines several times weekly. If not, consider an algae-based omega-3 supplement.

Zinc deficiency can also cause fatigue and reduced exercise performance. Meat is rich in highly absorbable zinc, while plant sources contain zinc that’s less easily absorbed. Pumpkin seeds, hemp seeds, and legumes provide zinc, but you need to eat them regularly and in substantial amounts.

Vitamin D deficiency is common in active people generally, but it’s worth checking since low vitamin D causes fatigue and muscle weakness. This isn’t specifically related to plant-based eating, but it’s worth addressing since you’re already dealing with energy problems. Most people benefit from vitamin D supplementation, especially during winter months.

Should I just go back to eating meat?

This depends on why you switched to plant-based eating in the first place. If you made the change for ethical or environmental reasons that are important to you, then learning to properly fuel a plant-based active lifestyle makes more sense than giving up on your values because the transition was harder than expected.

However, if you tried plant-based eating out of curiosity or because you thought it might be healthier, and your body is clearly telling you it’s not working well for you, there’s no shame in acknowledging that and returning to the diet that made you feel good and perform well. Not everyone thrives on the same diet, and your athletic performance and daily energy matter.

A middle ground might work better for you. Many athletes do well on predominantly plant-based diets that include fish several times weekly and occasional poultry or red meat. This provides the nutritional insurance of animal products while still emphasizing plants. You don’t have to be perfectly anything—you can eat in the way that makes your body feel and perform best.

Consider giving plant-based eating a proper try with adequate protein and nutrient supplementation before deciding. If you’re not eating enough protein, not supplementing B12, and potentially deficient in iron, you haven’t really given your body a fair chance to adapt. Making these changes and reassessing after a month might give you a clearer picture.

Some people genuinely do better including more animal products in their diets. Factors like genetics, gut health, absorption issues, and individual metabolism affect how well you extract and utilize nutrients from different foods. If you’ve tried everything and still feel terrible, your body might be telling you it needs animal products.

The fact that you used to run seven miles and lift weights while eating meat and vegetables suggests your body was thriving on that diet. If making it work plant-based requires enormous effort, constant supplementation, and you still feel terrible, the practical choice might be returning to what worked, even if it’s not the trendy option.

What does a properly fueled plant-based athletic diet look like?

A well-planned plant-based diet for athletes includes protein at every meal, plenty of carbohydrates to fuel training, adequate healthy fats, and strategic supplementation. Breakfast might include oatmeal with protein powder, nut butter, fruit, and seeds—providing carbs, protein, and healthy fats together.

Lunch needs a substantial protein source. A large bowl with quinoa or brown rice, a full cup of beans or lentils, roasted vegetables, avocado, and a tahini dressing provides balanced nutrition. Or a tofu scramble with whole grain toast and fruit. The key is making protein the centerpiece rather than an afterthought.

Dinner follows similar principles: a protein source like tempeh, fish, or legumes, a generous portion of carbohydrates from grains or starchy vegetables, plenty of colorful vegetables, and some healthy fats. This might look like baked fish with sweet potato, roasted broccoli, and a side of quinoa tossed with olive oil and herbs.

Snacks throughout the day keep your energy stable and help you meet protein targets. Hummus with vegetables and pita, trail mix with nuts and dried fruit, protein smoothies, Greek yogurt if you’re including dairy, or edamame all provide nutrients between meals.

Carbohydrate intake needs to be much higher than you might expect, especially around training. Active people need anywhere from three to seven grams of carbohydrates per pound of body weight daily depending on training intensity. That’s a lot of carbs, and hitting these targets on plant-based diets requires intentionally including grains, starchy vegetables, and fruit rather than relying mainly on leafy greens.

Your fat intake of twenty to thirty grams is too low for an active person. Healthy fats should comprise about twenty-five to thirty-five percent of your total calorie intake. This means adding avocado, nuts, seeds, olive oil, and fatty fish regularly. Fat isn’t the enemy—it’s essential for hormone production, vitamin absorption, and sustained energy.

How long does it take to adapt to plant-based eating?

The physical adaptation to plant-based eating happens at different rates for different aspects. Your digestive system adjusts to higher fiber intake within a few weeks, though this can cause temporary bloating and digestive discomfort. Your gut bacteria shift to better handle plant foods over one to three months.

However, adapting to plant-based eating while maintaining athletic performance requires more than just waiting for your body to adjust. If you’re not consuming adequate protein, iron, B vitamins, and calories, no amount of time will make you feel energetic and strong. Your body can’t adapt to insufficient nutrition—it just becomes increasingly depleted.

Some people report that their energy and performance improve after the initial transition period, once they’ve figured out how to properly fuel plant-based training. This typically takes one to three months of eating adequately, not one to three months of struggling with low energy hoping it gets better on its own.

The key indicator is whether you’re trending toward feeling better or continuing to feel worse. If after a few weeks of intentionally eating more protein, taking supplements, and fueling workouts properly, you’re starting to feel improvements, that suggests you’re on the right track. If you’re still declining despite making these changes, something isn’t working.

Your previous athletic performance gives you a baseline. If you were running seven miles and lifting weights successfully on your previous diet, you should eventually be able to return to similar performance levels on a well-planned plant-based diet. If after two to three months of proper nutrition you’re still struggling, that might indicate plant-based eating isn’t optimal for your body.

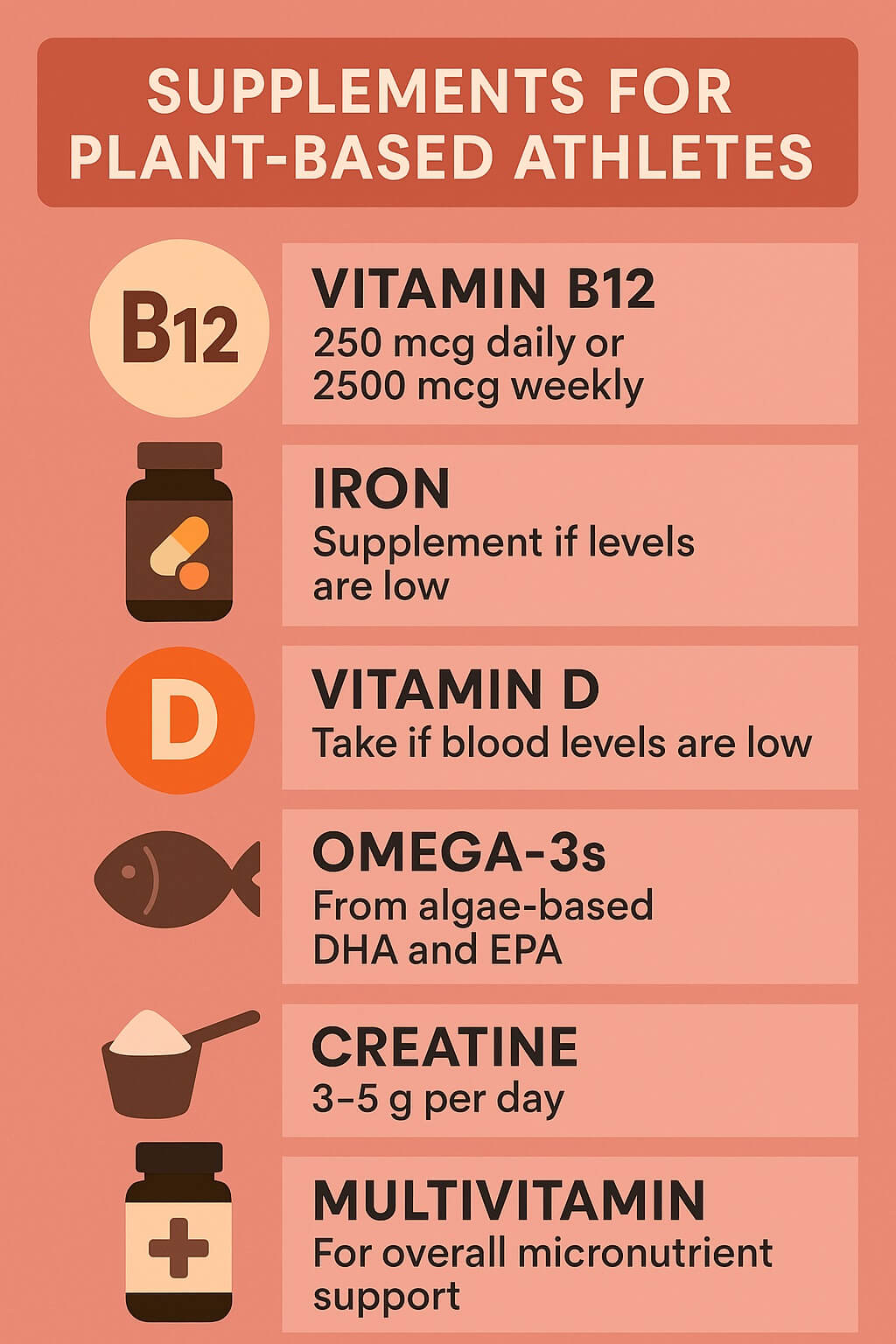

What supplements should plant-based athletes take?

Vitamin B12 is absolutely essential for anyone eating plant-based. Take a daily supplement of at least 250 micrograms or a weekly supplement of 2500 micrograms. This prevents deficiency that causes fatigue, weakness, neurological problems, and anemia. There’s no debate about this one—supplementation is required.

Iron supplementation might be necessary, especially if you’re experiencing significant fatigue. However, don’t start taking iron without testing your levels first, as excess iron can cause problems. Ask your doctor to check your ferritin levels, which indicate your iron stores. If you’re low, supplementation along with dietary changes can dramatically improve your energy.

Vitamin D should be tested and supplemented if needed. Most people, regardless of diet type, need vitamin D supplementation, especially if they live in northern climates or don’t spend much time outdoors. This affects energy, immune function, bone health, and mood.

Omega-3 supplementation with algae-based DHA and EPA helps if you’re not eating fatty fish regularly. These omega-3s are crucial for heart health, brain function, and managing inflammation from training. Plant-based sources like flax don’t adequately replace EPA and DHA, so supplementation fills this gap.

Creatine monohydrate supplementation can significantly improve high-intensity exercise performance, especially for plant-based athletes. Creatine occurs naturally in meat, and people who don’t eat meat have lower creatine stores. Supplementing with three to five grams daily can improve strength, power, and recovery.

A multivitamin designed for athletes provides insurance against deficiencies in zinc, iodine, selenium, and other micronutrients that might be lower on plant-based diets. While it’s not a substitute for eating well, it helps fill gaps that are easy to miss when you’re figuring out a new way of eating.

When should I see a doctor about my energy problems?

If you’ve been experiencing severe fatigue for more than a few weeks, especially if it’s affecting your ability to work, exercise, or function normally, getting bloodwork is worthwhile. Your doctor can check for iron deficiency anemia, B12 deficiency, thyroid problems, and other medical issues that cause fatigue.

Explain to your doctor that you recently changed your diet and are concerned about nutritional deficiencies. Be specific about what you’re eating and your activity level. Many doctors aren’t well-versed in sports nutrition or plant-based diets, so providing context helps them understand what tests might be most useful.

Request specific tests beyond a basic metabolic panel. Ask for ferritin (iron stores), complete blood count (checks for anemia), B12, vitamin D, and thyroid function tests at minimum. If your insurance covers it, comprehensive micronutrient testing can identify multiple deficiencies at once.

Severe fatigue that came on suddenly with dietary changes is less likely to be a serious medical condition and more likely related to inadequate nutrition, but it’s still worth ruling out other causes. Thyroid problems, chronic fatigue syndrome, autoimmune conditions, and other issues can cause similar symptoms.

If bloodwork reveals deficiencies, work with your doctor or a registered dietitian who specializes in plant-based nutrition to correct them. Sometimes prescription-strength supplements are necessary initially to replenish depleted stores, especially with iron or B12.

Don’t ignore symptoms or assume you just need to push through. Severe fatigue and declining athletic performance are your body’s way of telling you something is wrong. Whether the solution is dietary changes, supplementation, or medical treatment, addressing the problem promptly prevents more serious issues from developing.

What’s the bottom line on plant-based eating and athletic performance?

Plant-based diets can absolutely support high-level athletic performance, but they require more intentional planning than diets that include animal products. You can’t just remove meat and expect to feel the same while eating mostly vegetables and small amounts of protein. Your body needs substantial protein, adequate calories, proper supplementation, and strategic nutrient timing.

If you’re feeling terrible on your current approach, something needs to change. Either commit to properly fueling a plant-based athletic diet with sufficient protein, calories, and supplements, or consider whether including more animal products makes practical sense for your goals and lifestyle.

There’s no moral superiority in struggling through a dietary approach that makes you feel awful and tanks your performance. Your health and wellbeing matter, and the diet that makes you feel energetic, strong, and capable is the right diet for you, regardless of what’s trendy or what others think you should eat.

Listen to your body, but also educate yourself about proper plant-based sports nutrition so you’re giving this approach a fair trial. If after making genuine efforts to eat adequately you still feel terrible, that’s valuable information about what your body needs.

The diet you thrived on before—eating meat and vegetables with sufficient protein to support running seven miles and lifting weights—proved it worked for your body. If plant-based eating with proper planning doesn’t eventually return you to similar performance and energy levels, there’s wisdom in returning to what worked, possibly with some plant-based principles incorporated.